US Airborne Pathfinders in World War II

The Parachute Scout Company of the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, in North Africa. (US Army)

During World War II, it was very difficult for troop carrier aircraft to navigate precisely to the landing zones planned for their paratroopers and gliders, particularly at night.

In June 1942, the British established a specially trained unit of Pathfinder paratroopers to locate and mark out landing zones ahead of the main Airborne assault forces. It deployed North Africa in May 1943.

In November 1942, the US Army deployed the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), to North Africa as part of Operation TORCH, the Allied invasion of North Africa. In March 1943, a 'Parachute Scout Company' was formed in this Battalion to serve as its Pathfinders in the Mediterranean theatre.

OPERATION HUSKY: SICILY

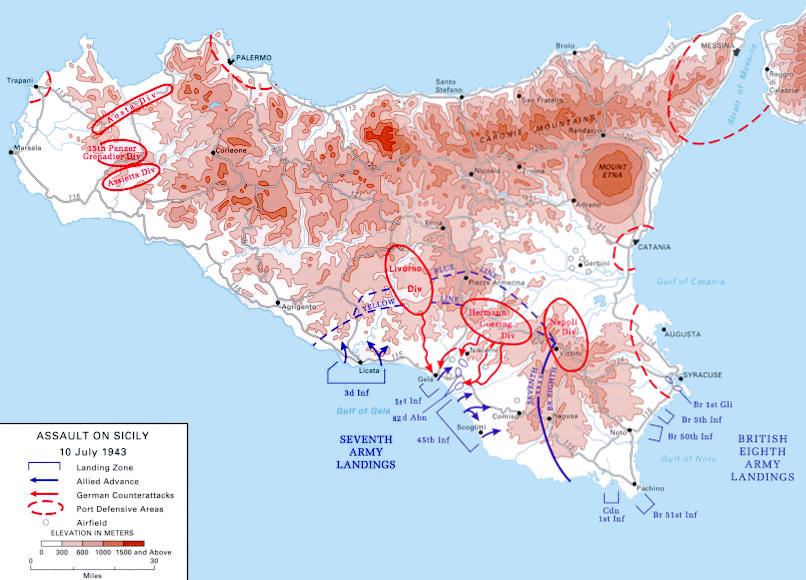

Operation HUSKY, 10 July 1943: the planned Allied landings on Sicily. (US Army, public domain)

Members of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in Sicily in July, 1943. (US Army)

The 82nd Airborne Division arrived in North Africa from the United States in May 1943 and the 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR, was attached to it. However, senior officers of the 82nd Airborne did not feel the need for Pathfinders for the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 (Operation HUSKY). Although this was an error of judgement, it did not have disastrous consequences because the troop carrier aircraft had become so widely scattered on their route into the island that many would in any case have been outside the range of any Pathfinder equipment on the dropzones.

The initiative and courage of the airborne troops were so outstanding that that they still managed to achieve most of their objectives, despite their disastrous delivery. Even so, there was serious criticism of the overall Troop Carrier/Airborne performance at high levels. Senior US Army officers were convinced that successful large-scale airborne operations could not be achieved. There were even suggestions that the Airborne Divisions should be disbanded.

Careful analysis of the airborne operation was carried out and a number of recommendations were made for future airborne planning, including that specially trained Pathfinders should be used to locate and mark out the drop and landing zones. Every effort would be made to ensure that these recommendations were implemented in time for the assault on Western Europe.

Despite the criticisms, the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, Major General Matthew Ridgway, and the commander of the US Northwest African Air Force Troop Carrier Command, Brigadier General Paul Williams, lobbied strongly to continue large-scale airborne operations. They were allowed to do so.

Major General Matthew Ridgway (centre left), Commanding General, 82nd Airborne Division, and staff, overlooking the battlefield near Ribera, Sicily, 25 July 1943. (Public Domain)

Major General Paul Williams, Commander, US Ninth Troop Carrier Command. (Official Photo, USAAF - Wings at War No. 4: Airborne Assault on Holland, p. 19; public domain)

OPERATION AVALANCHE: SALERNO

Salerno, 9 September 1943 (Operation Avalanche): British troops and vehicles are unloaded from a Landing Ship Tank onto the beaches. (IWM NA 6630)

To reduce the risk of navigational disasters in the future, US commanders decided to expand the small US pathfinding capability and to incorporate it into future operational plans. As a result, Lieutenant William Jones of the 82nd Airborne became the first US Pathfinder to jump into action when he landed as part of a night airborne reinforcement of the Salerno beachhead on 13 September 1943.

The success of the Airborne troops in the Salerno beachhead helped improve their standing and it was decided to allocate them critical tasks in the invasion of Western Europe.

US ARMY'S FIRST PATHFINDER SCHOOL: SICILY

Three paratroopers of the US 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, relax after a hard time in Sicily. (IWM NA 4347)

The disaster in Sicily made the US Airborne commanders realize that Pathfinders would be an essential component of any future airborne assault. Both aircrew and paratroopers would need to be selected and trained for this crucial specialized task.

Towards the end of summer 1943, a number of meetings were held in Sicily between individuals who became key players in the development of the Pathfinders. These included Colonel James Gavin, Commanding Officer of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch, Operations Officer of the US 52nd Troop Carrier Wing; and Major Bernard 'Boy' Wilson, Commanding Officer of the British 21st Independent Parachute Company, the Pathfinders of the British 1st Airborne Division.

During the meetings, the idea emerged of establishing a Pathfinder School for US Airborne troops. Maj Wilson was able to provide advice on techniques and equipment, as the British had set up the 21st Independent Parachute Company as a permanent Pathfinder unit over one year earlier. In contrast to the formed-unit approach adopted by the British, the Americans chose to carry out a fresh trawl for Pathfinder volunteers for each operation (although some volunteered for more than one operation).

As a result of these meetings, the Americans established a Pathfinder training course at the US Fifth Army Airborne Training Center in Sicily to train Pathfinders for the Mediterranean theatre. Its first trainees were volunteers from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division.

Major General James Gavin. (US Army)

Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch. (US Army)

Major Bernard ‘Boy’ Wilson, Officer Commanding, 21st Independent Parachute Company. (Pegasus Archive)

IX TROOP CARRIER COMMAND PATHFINDER SCHOOL: ENGLAND

(The US Army Air Force used Roman numerals in some organizational names during World War II; in this case, 'IX' is the Roman numeral for '9').

Sleeve insignia worn by members of IX Troop Carrier Command before August 1944. (Public domain)

Pathfinders would also be needed for the US contribution to the airborne assault on Western Europe. The task of training and operating the US Pathfinders fell to IX Troop Carrier Command of the US Ninth Air Force, which had arrived in the United Kingdom from the Mediterranean theatre in October 1943.

The Pathfinder concept was now accepted, and IX Troop Carrier Command established its own Pathfinder School at RAF Cottesmore, Rutland, on 28 February 1944.

With his Pathfinder experience in the Mediterranean, Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch was the natural choice to take command. He was also a very experienced C-47 pilot, having flown DC-3 airliners – the civilian equivalent of the C-47 troop carrier aircraft - for United Airlines before the war.

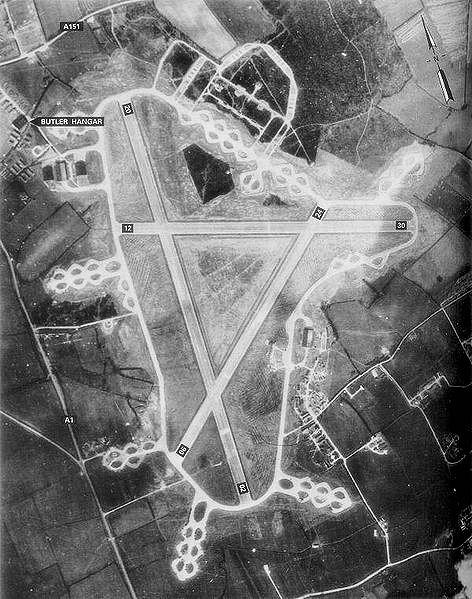

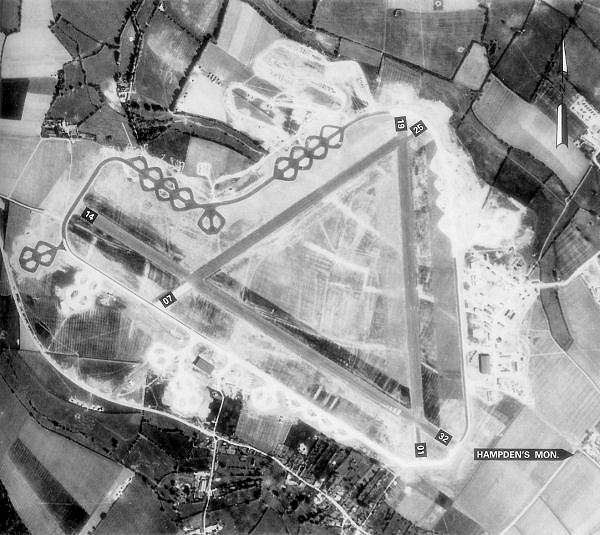

A photo of RAF North Witham taken on 19 March 1944, just before the arrival of the Pathfinder School from RAF Cottesmore. The A1 (then called the Great North Road) is visible along the left side of the image. The airfield is known today as Twyford Woods and is owned by Forestry England, which encourages walkers to enjoy its woodland and the historic landscape. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NorthWitham-19mar44.jpg, marked as public domain)

RAF Cottesmore soon became overcrowded as other Troop Carrier units moved in, so the Pathfinder School moved to RAF North Witham, Lincolnshire, on 22 March 1944.

Suitable aircrew candidates were selected from all three Troop Carrier Wings and trainee Pathfinder paratroopers were drawn from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. Each of these Divisions created its own Provisional Pathfinder Company of around 180 trainees. Captain Neal McRoberts was put in command of the 82nd Airborne's Provisional Pathfinder Company, while Captain Frank Lillyman commanded that of the 101st Airborne Division.

Captain Frank Lillyman, commander of the 101st Airborne Division Pathfinders. (US Army, public domain)

Captain Neal McRoberts, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division Pathfinders on D-Day.

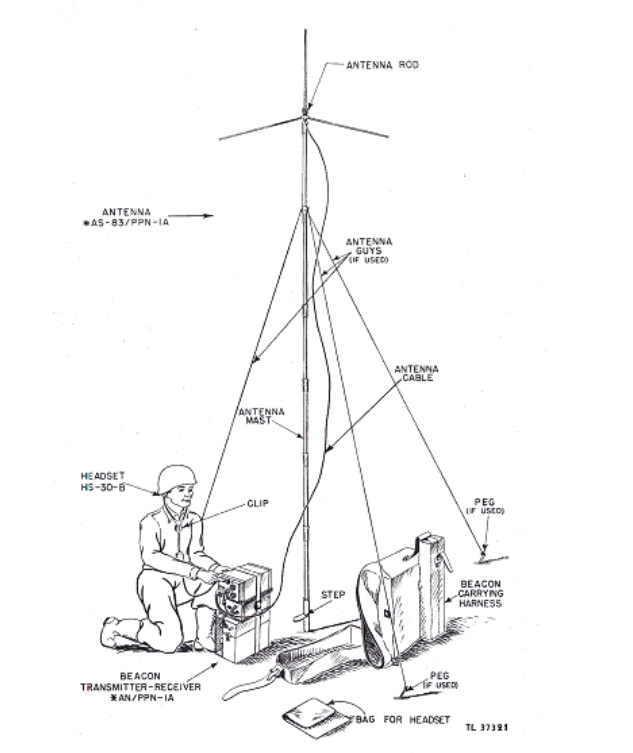

A diagram taken from the official US Army operating manual for the AN/PPN-1A Eureka Beacon. (US Army, public domain)

A number of the paratroopers were 'volunteered' by their commanders, who seized the chance to dispose of troublesome individuals. These were often men who were difficult to discipline in daily military life but were excellent in combat.

A Pathfinder team was made up of men from the same battalion. It was intended that they would mark the drop and landing zones for their parent battalion and then return to it for combat duty after their Pathfinder tasks had been completed. Their 'contract' as a Pathfinder would be fulfilled at that point but they could volunteer for future missions if they wished.

The size of each Pathfinder team varied according to its individual tasking but they were generally made up of two officers, two Eureka beacon operators, eight men operating marker lights, and four to six men to provide defence.

A 'flaming torch' Pathfinder badge awarded to Pathfinder students - both aircrew and paratroopers – upon successful completion of the Pathfinder training course. It was worn on the lower left arm. This original badge was worn by Private William Wheeler, a pathfinder in the 101st Airborne Division. (Richardelainechambers (talk) (Uploads), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During the course at North Witham, both aircrew and paratroopers worked hard together to refine procedures and techniques to be used on D-Day. Lieutenant Colonel Crouch was keen to foster a team-spirit between the aircrew and paratroopers. As an experienced pre-war airline pilot, he well understood the need for close teamwork on board the aircraft. He employed a number of techniques to encourage teamwork in high-stress situations:

- Each team of paratroopers was assigned to a particular aircraft and crew, and they would train, eat and live together as a team.

- He scheduled his aircrew for three practice missions per day to accustom them to high-tempo operations.

- Navigators were purposely disorientated so they could get used to working under stress.

- Prize money and a 48-hour pass to London was awarded to the crew that could drop a dummy by parachute closest to a marker on a dropzone.

- All Pathfinder officers – both aircrew and paratroopers – underwent an orientation course, so each could understand the problems of the other. The pilots carried out at least one parachute jump with the men they would carry into action, and the paratroopers were shown how to start and taxi a C-47 aircraft, and learned about aerial navigation.

Lieutenant Colonel Crouch made nine parachute jumps himself. This incurred the anger of his commanders, who were concerned about losing aircrew in parachuting accidents. In reply, Crouch insisted that the high number of sprained ankles suffered by his pilots had occurred when they jumped from the back of the trucks on return to barracks after training missions.

The paratrooper trainees jumped five to seven times per week, with at least two drops at night, and were taught how to use electronic beacons, signalling lights, smoke and luminous panels to mark out the landing zones. Trainees were awarded the Pathfinder badge – a flaming torch – upon successful completion of the course and it was worn on the lower left sleeve.

Operation NEPTUNE: Normandy, 6 June 1944

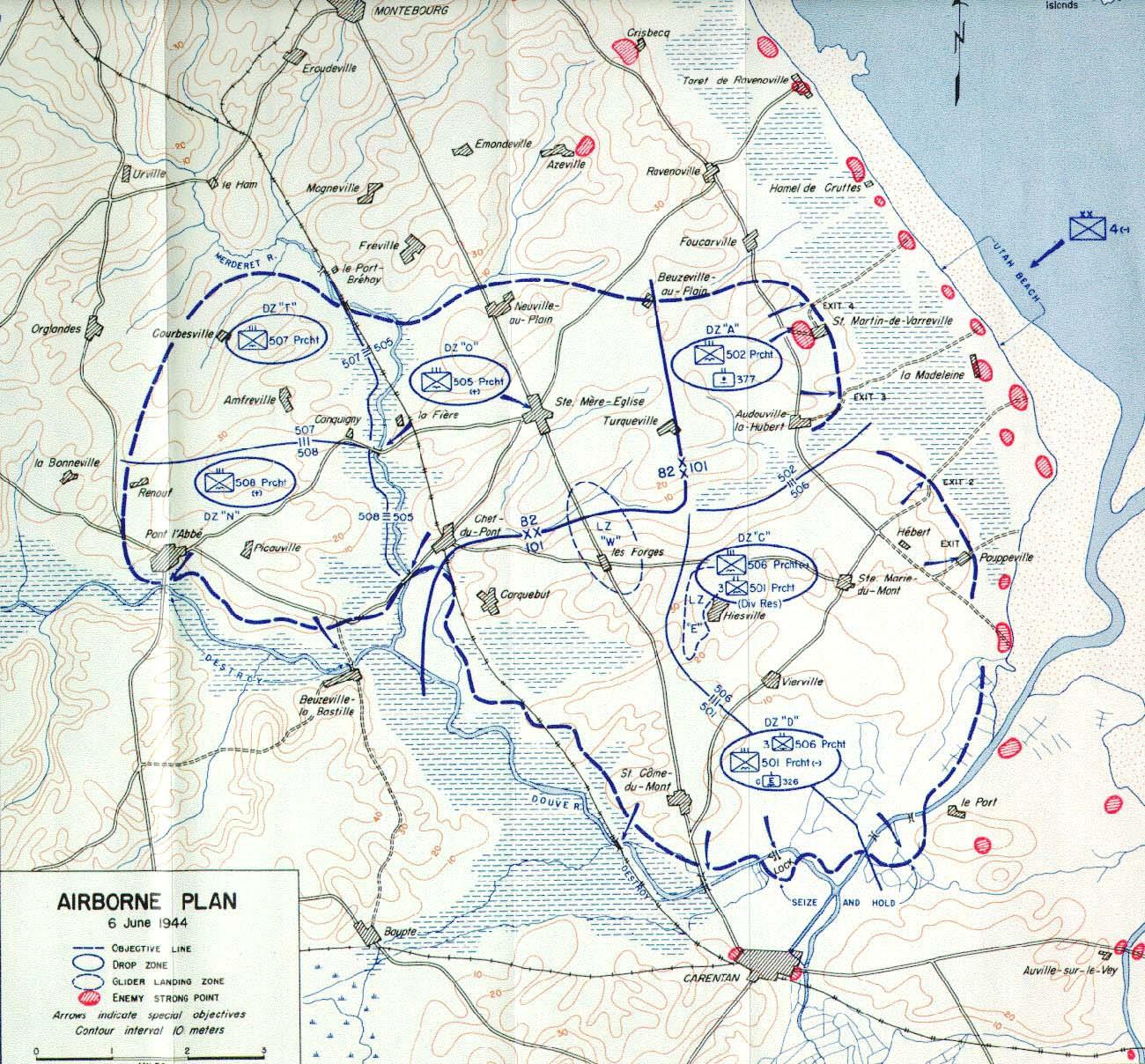

The planned US airborne dropzones on the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy, D-Day, 6 June 1944. (Historical Division, US Department of the Army, public domain)

The first Pathfinder C-47 takes off from North Witham at 2145 hrs, British Double Summer Time, on 5 June 1944, heading west over the the Great North road (A1) and then to Normandy. It is flown by Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch, commander of the US Airborne Pathfinder School. On board are Pathfinders of the US 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Captain Frank Lillyman, who would land slightly off target at Saint Germaine-de-Varreville. Their marker lights and Eureka beacon would be in operation on the scheduled time but at a point approximately one mile north of their intended dropzone.

The high standards of training were tested in various exercises, but the real combat test began at 21.54 hrs Double British Summer Time on 5 June 1944, when the first Pathfinder C-47 aircraft lifted off from runway 30 at North Witham, flown by Lieutenant Colonel Crouch and Captain Vito Pedone. It was followed by 19 more aircraft over the next hour, each filled with trained Pathfinders of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

Operation NEPTUNE - the airborne and seaborne assault on Normandy - was underway.

Map showing the planned flight routes over Normandy for the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions on Operation NEPTUNE, 6 June 1944. (US Air Force, public domain)

On approaching France, the Pathfinder pilots were surprised by an unexpected bank of clouds that extended from the western shores of the Cotentin peninsula almost to the drop area. This disrupted navigation to the extent that only two batches of Pathfinders were dropped close to their targets: those of the 101st Airborne allocated to mark Dropzone C, and those of the 82nd Airborne allocated to Dropzone O.

The Pathfinders for the remaining four dropzones were dropped so far away from their targets that they did not have enough time after their landing to reach their planned landing zones. Some teams decided to set up their guiding equipment wherever they could, in an effort to achieve concentration of their battalions in one area. Not all of the teams were able to set up their marker lights because German troops were too close, and they could only use their Eureka beacons for guiding the aircraft to the zones. When the Pathfinders had completed their marking tasks, they sought to re-join their parent battalions and resume their infantry roles.

Paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division pause for a rest near the church in St Marcouf, 6 June 1944. (US Army photo, public domain)

As in the Mediterranean, the airborne troops' initiative and courage over the next few days were outstanding. Despite widespread scattering, they managed to combine themselves into temporary groups and pressed on to achieve most of their objectives over the following few hours. Ironically, the widespread scattering of the drops helped deceive the Germans into believing that the airborne assault force was bigger than it actually was.

A group of paratroopers from the US 101st Airborne Division proudly display a captured enemy flag at Marmion Farm, Ravenoville, 6 June 1944. (US Army photo, public domain)

The Pathfinders took some heavy casualties on D-Day but these were not evenly distributed among units. For example, a few Pathfinders of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (82nd Airborne Division) suffered jump injuries but no combat fatalities, as there was negligible opposition where they landed; in contrast, the 508th Pathfinders lost approximately two-thirds of their men.1

- 1

Jeff Moran, American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II (Atglen, PA, 2004), 40.

Smiles of relief: Lt Col Crouch and his crew on return from their D-Day mission to Normandy on 6 June 1944. L-R: Cpl Harold E Conrad, radio operator; Capt Edward E Cannon; Capt William Culp, navigator; Capt Vito S Pedone co-pilot, Lt Col Joel L Crouch pilot. (Via Steve Pedone)

US Troop Carrier aircraft had been sent to Normandy with 13,348 US paratroopers on board; later analysis of drop reports gave an indication of how far from their targets some of the paratroops had landed 2:

- On the target dropzone: over 10%.

- Up to 1 mile of the target zone or Pathfinder beacon: 25%- 30%.

- 1 to 2 miles away from their zones or beacons: 15%-20%.

- 2 to 5 miles away from their zones or beacons: about 25%.

- 5 to 10 miles away from their zones or beacons: about 10%.

- 10 to 25 miles from their zones or beacons: 4%.

- Missing: 6%.

The wide dispersal of the paratroopers prompted senior officers once again to query the value of night parachute operations. Was drop accuracy or protection by darkness more important? It was soon concluded that accurate navigation was the priority and, as a result, all large-scale airborne assaults were carried out in daylight for the rest of the war.

After Operation NEPTUNE, the Pathfinder School at North Witham began training Polish airborne troops belonging to the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. This Brigade would be attached to the British 1st Airborne Division for Operation MARKET GARDEN in the Netherlands in September 1944. As it happened, these Polish Pathfinders were not used in the Brigade's drop on 21 September.

Apart from continuing training, the expertise of IX Troop Carrier Command's Pathfinders would be needed in the Mediterranean before their next major European operation.

- 2

John C Warren, Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942-45, Defense Technical Information Center (Air University, Maxwell AFB, Alabama, September 1955) <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA522511.pdf> [accessed 2019].

Operation DRAGOON - Southern France

Map of the area of southern France where the airborne and seaborne landings of Operation DRAGOON took place. (US Army, public domain)

The Allies decided to invade southern France to gain important ports for the delivery of supplies from the USA and to open up another thrust into enemy-occupied territory. The aim was for Allied forces to push northwards from the French Riviera into the French heartland, and eventually join up with the Allied armies moving eastwards from Normandy.

The invasion – codenamed Operation DRAGOON – was set for 15 August 1944. It would comprise an airborne and seaborne assault. To boost the number of troop carrier C-47s available for DRAGOON, the 50th and 53rd Troop Carrier Wings in England sent 413 of them to Italy. 3

By now, Pathfinders were considered vital for a successful airborne assault, so experienced Pathfinder paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were sent with their equipment to Marcigliana airfield to train locally based US paratroopers in Pathfinder techniques. In addition, 12 Pathfinder C-47s and their aircrew were sent.

At 1.00am on 15 August 1944, nine Pathfinder aircraft took off from Marcigliana, carrying nine teams of US and British paratroopers (121 paratroopers in total) to mark three zones, two American and one British. 4 The aircraft reached the French coast on schedule and approximately on course, but a thick blanket of fog played havoc with navigation inland.

CG-4A gliders under tow by Douglas C47 Dakota aircraft heading for southern France during Operation DRAGOON. (Public domain, via Australian War Memorial SUK12892)

The navigational aids on board the Pathfinder C-47s did not prevent wide scattering of the Pathfinder paratroopers. Only two of the nine teams were dropped on or close to their intended targets. The British Pathfinders were dropped accurately on their assigned dropzone and were able to set up their navigational aids according to plan. On one US zone, some Pathfinders were dropped prematurely but were close enough to set up their navigational aids in time for some missions later in the day. On the other US zone, the Pathfinders were dropped more than 10 miles away from their target and were unable to complete their mission.

Nonetheless, many of the main force of British paratroopers were not dropped on the intended zone, despite the accuracy of their Pathfinder drop and deployment of navigational aids. This showed that it was still important that aircrew could visually identify landmarks from the air, in addition to receiving guidance from electronic aids.

Despite the widespread scattering of the paratroopers, all the objectives of the Allied airborne forces were achieved within 48 hours of their landings, and the foothold in southern France was consolidated. This was to be the final Allied airborne operation in the Mediterranean theatre during the war, with the various component forces being reassigned throughout their respective national armies.

Operation MARKET GARDEN: Netherlands

Chalgrove airfield, 1944. (US Air Force, public domain)

On 14 September 1944, the status of the Pathfinders was enhanced when the Pathfinder School was transformed into an independent operational unit, the IX Troop Carrier Command Pathfinder Group (Provisional), with Lieutenant Colonel Crouch remaining in command. This showed the importance of the Pathfinder concept had finally been accepted. On the same day, the Pathfinders moved from North Witham to Chalgrove in Oxfordshire. The move would come just three days before the next major Allied airborne operation was launched on 17 September 1944: Operation MARKET GARDEN.

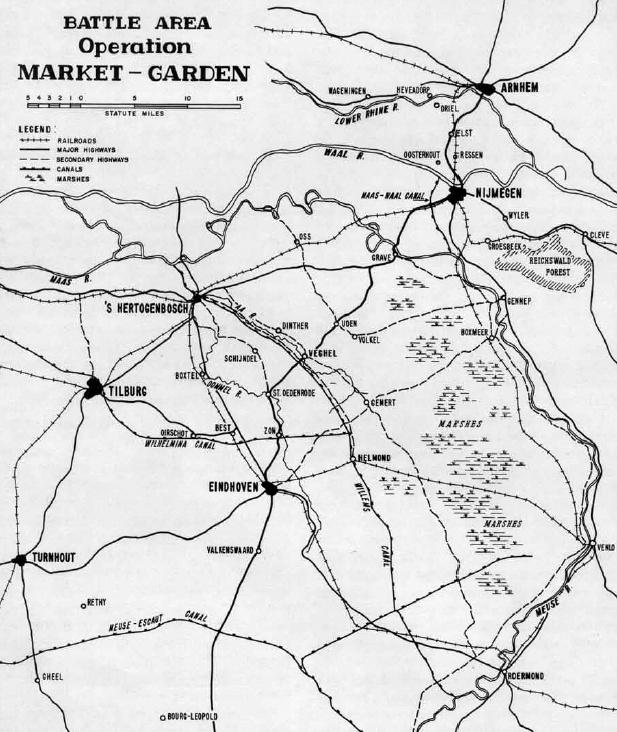

The major highway linking Eindhoven – Nijmegen – Arnhem would become known as ‘Hell’s Highway’ during Operation MARKET GARDEN. (US Air Force, public domain)

Operation MARKET GARDEN's aim was for a 'carpet' of airborne troops to be landed near Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem in the Netherlands to capture and secure key bridges over rivers, so that follow-up British ground forces could drive northwards from their frontline in Belgium. Within Operation MARKET GARDEN, the airborne assault was known as Operation MARKET, while the ground assault was known as Operation GARDEN. If successful, these operations would allow Allied ground forces to sweep north to Arnhem and then pivot eastwards towards the crucial industrial Ruhr region of Germany.

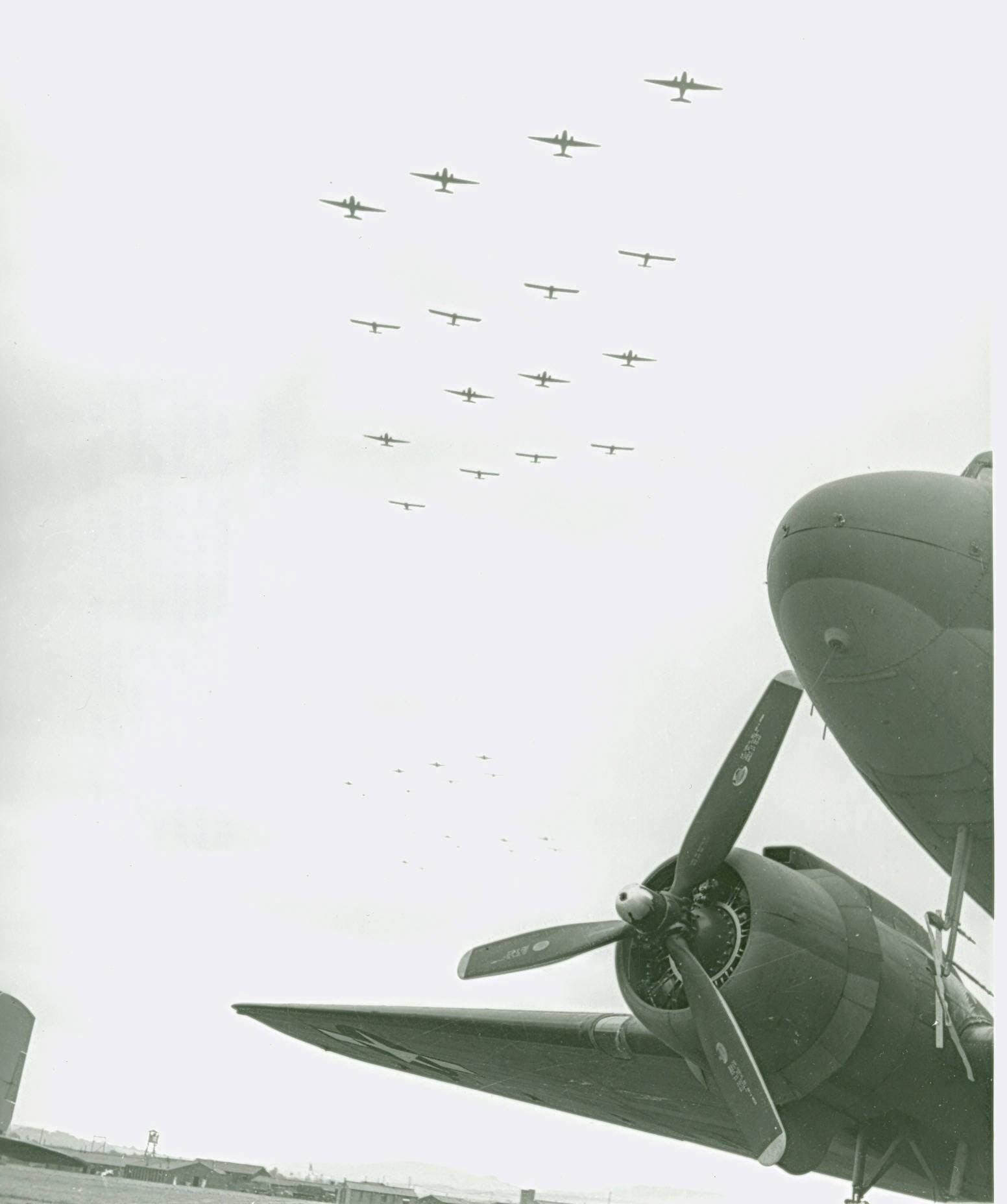

C-47s towing CG-4A gliders US Army. (Public domain)

Only small numbers of US Pathfinders were used to support the 82nd and 101st Airborne landings near Nijmegen and Eindhoven. At 1025 am on 17 September 1944, the first pair of Pathfinder C-47 aircraft took off from Chalgrove, followed at ten-minute intervals by the other two pairs. 5

The Pathfinders of the 82nd Division were in the lead and had an easy trip as far as Grave before anti-aircraft batteries opened up on them. They were under intense fire as they made their drop at 1247 pm from an altitude of 500 feet. The two pathfinder teams landed side by side in open fields about 500 yards north of dropzone. While one team stood guard, the other set up its equipment: its high-visibility panels were laid, and beacons were operating within three minutes. 6

The Pathfinders of the 101st Division had a harder time. Their aircraft ran into heavy fire over the German lines. Evasive action was forbidden, so all the pilots could do was to speed up to 180 mph. One aircraft heading to dropzone A was shot down near Ratie, leaving only one Pathfinder team to mark that dropzone. Fortunately, the remaining aircraft reached the dropzone and also dropped its team at 1247pm. The paratroops met no resistance and were able to put the Eureka in operation in a minute and to lay out the panels in 21/2 minutes. They had trouble with the radio antenna but had that set working within five minutes. 7

The other Pathfinder teams of the 101st Airborne were tasked with marking dropzones B and C. They dropped with pinpoint accuracy at 1254pm. The Eureka beacon was in action in less than one minute, and panels and radio were ready within four minutes.

The Pathfinders' mission was highly successful, allowing the main airborne assault forces to land in their planned areas. Powerful Allied air support had cleared the path for the American and British troop carriers and the initial landings had been successful beyond all expectations. The airborne commanders were unanimously enthusiastic in their praise of the accurate and efficient delivery of their troops.

'BATTLE OF THE BULGE': ARDENNES, BELGIUM

On 16 December 1944, German ground forces launched Operation WACHT AM RHEIN (WATCH ON THE RHINE). German units attacked US forces in the Ardennes region of Belgium, aiming to drive a wedge between the British and US Armies and recapture the port of Antwerp, which was vital to the flow of supplies to Allied forces.

This map shows the extent to which the German forces punched through the Allied lines in the Ardennes region in December 1944. (US Army, public domain)

German forces made deep inroads into US lines, but they could not capture the vital road junction town of Bastogne, which was held by the US 101st Airborne Division. The town was besieged and there was an urgent need for supplies to be air-dropped to the 101st.

At 11.30am on 22 December, the call went to the Pathfinders at Chalgrove to launch an immediate two-plane operation to Bastogne. Their mission would be to drop into the US perimeter at Bastogne and coordinate resupply drops into the perimeter.

At the time, there were no permanently assigned Pathfinder paratroopers at Chalgrove but – by amazingly good luck – there was a Pathfinder training course being run for student paratroopers. Despite virtually no notice, two teams of Pathfinders were selected and prepared, and took off at 2.52pm. However, the aircraft were recalled because weather and time did not permit subsequent resupply missions to fly that day, and the mission was rescheduled for the next day.

At 6.45am on 23 December, the aircraft took off again and successfully delivered the Pathfinders to the planned drop zone. Lt Col Joel Crouch was flying the lead aircraft, and he checked the results of their work by flying back on course half-an-hour after dropping the Pathfinders, using the aids as set up by the team on the ground.

A Pathfinder operates a Eureka beacon on top of a pile of bricks at Bastogne on 23 December 1944. He is guiding in troop carrier aircraft bringing desperately needed supplies to the surrounded US 101st Airborne Division. (US Army, public domain)

During the emergency resupply period, which lasted until 27 December 1944, a total of 911 aircraft parachuted supplies to the beleaguered 101st Airborne, with a further 61 aircraft towing gliders to land within its defended perimeter.

IX Troop Carrier Command concluded that the Pathfinders and their specialist equipment played a key role in the successful resupply of the 101st Airborne Division, thereby preventing the Germans from capturing Bastogne.

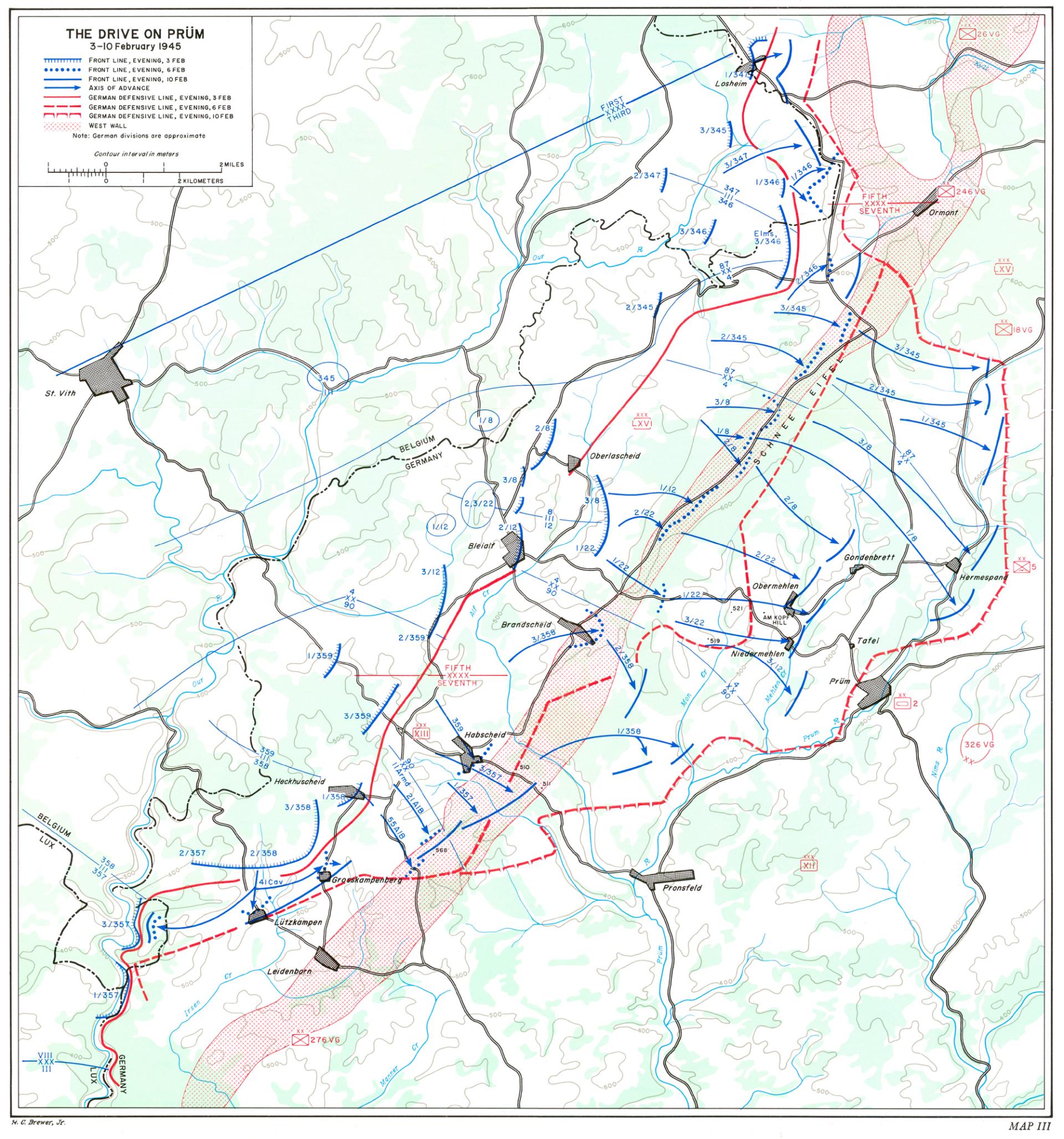

Prüm, Germany

This map shows the advance into Germany by US forces during early February 1945. The town of Prüm was captured by the US 4th Infantry Division but they became cut off from their supplies because bridges and roads along the supply routes had been washed away by heavy rains and early thawing. An airborne re-supply became essential. (US Army, public domain)

In early 1945, airborne resupply was called for again as US troops advanced into Germany. Elements of the 4th Infantry Division had captured the town of Prüm but found themselves cut off from their supplies because the bridges and roads along the lines of communication had been washed away by heavy rain and early thawing.

On 13 February 1945, a team of Pathfinders from the 101st Airborne dropped into the area and coordinated resupply missions to a dropzone selected nearby at Bleialf. As a result of the Pathfinders' successful operation, over 243 tons of supplies were received by the cut-off troops.

OPERATION VARSITY: GERMANY

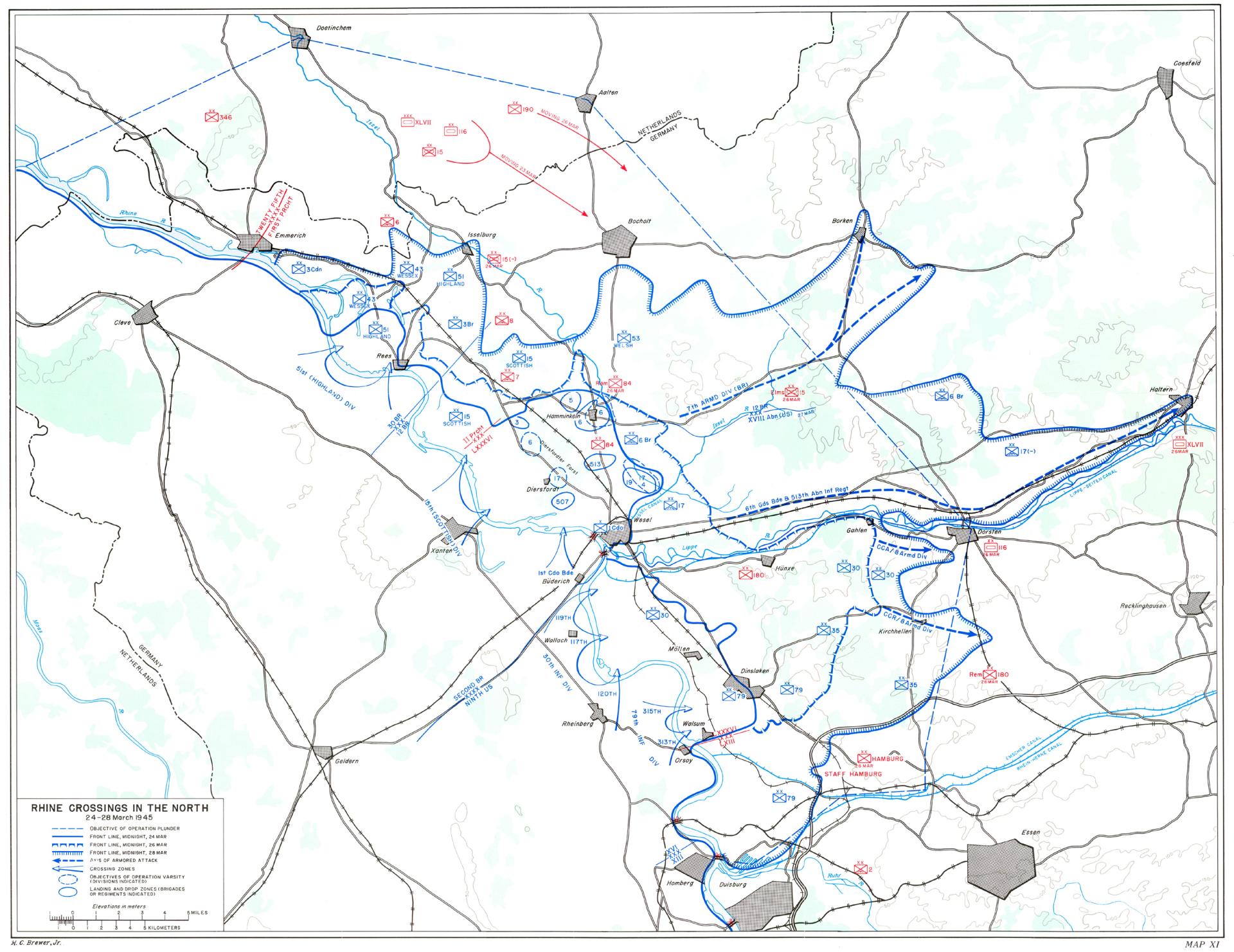

In March 1945, the Pathfinders moved from Chalgrove to Chartres airfield in France, which would be their final location in Europe before the war ended. They would be used in just one more operation before the final German surrender in May 1945: Operation VARSITY, the airborne landings on the east bank of the River Rhine near Wesel on 24 March 1945.

Operation VARSITY would be carried out on 24 March 1945 in support of Operation PLUNDER, the amphibious landings of British, US and Canadian troops on the east bank of the River Rhine. Two airborne divisions would be involved: the British 6th Airborne Division – a veteran of D-Day and the battle for Normandy – and the US 17th Airborne Division.

Map of the Allied crossings of the Rhine in the area around Wesel during 24-28 March 1945. (US Army, public domain)

The US 17th Airborne Division had arrived in England in August 1944. The 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment – which had seen action in Normandy with the 82nd Airborne Division – was transferred to the 17th Airborne Division to boost the levels of combat experience within it. The Division first saw combat in January 1945 in the Ardennes.

The 17th Airborne Division created just one team of 12 Pathfinders during the war. Some of these men were 'volunteered' as Pathfinders because of their disciplinary history. They were sent to train first with Normandy veterans of the 82nd Airborne and 101st Airborne Divisions, before moving to Chalgrove; their training lasted around three months in total.

Operation VARSITY would be a daylight operation. The Pathfinders would not be dropped ahead of the main force for a variety of reasons:

- Navigation was not expected to be a problem in daylight with the Rhine as an obvious terrain feature and Pathfinder equipment would be deployed on the American-held side of the Rhine.

- The complexity of the routeing of the air armada, which would be converging from airfields in England and France.

- The suicidal nature of dropping small numbers of paratroopers on heavily defended dropzones.

- The compromise of any surprise by the early arrival of the Pathfinders.

- The scale of the assault required every possible aircraft to carry troops, so Pathfinder Group aircraft – led by Lt Col Joel Crouch - were used to carry paratroops of the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment instead of the usual Pathfinder teams.

C-47s release hundreds of paratroops and their supplies over the Rees-Wesel area to the east of the Rhine during Operation VARSITY, 24 March 1945. (US Army, public domain)

On 24 March 1945, some of the Pathfinders set up their equipment in friendly territory on the west bank of the Rhine to guide their comrades to the dropzones on the enemy side of the river. Other Pathfinders from the Division flew in the lead aircraft of each wave and jumped with the first troops; once landed, they laid out high-visibility panels and smoke markers to help guide the rest of the force.

Poor visibility - caused by the smoke screen laid to assist the simultaneous amphibious crossing of the Rhine - contributed to some serious navigational errors. Although the Eureka beacons performed well (they could be detected from 16 miles away), visual aids on the friendly side of the Rhine were at times obscured by the smoke. On the enemy side of the river, the haze and smoke made visual navigation difficult; although compass and Gee transmissions might guide the aircraft towards the dropzones, it was essential for pilots to visually identify their dropzones to ensure drop accuracy.

Despite the challenges, the landings in VARSITY were more accurate than those in Operations NEPTUNE and MARKET, with the vast majority of paratroops and gliders landing within two miles of their zones.

There would be no more large-scale operations before the war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945. The continued existence of the Pathfinders could not be justified, and it was not long before their personnel and equipment were reassigned to the units from which they had originated.

THE PACIFIC

In the Pacific theatre, the US 11th Airborne Division also employed Pathfinders in two successful operations on Luzon in the Philippine Islands in early 1945. One team moved through enemy lines on foot and the other landed by boat to locate and mark dropzones for the assaulting parachute forces.

Paratroopers of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment prepare for their combat jump on Tagaytay Ridge, Luzon, Philippines, on 3 February 1945. (US Army Signal Corps, public domain)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bando, Mark, The 101st Airborne at Normandy (Osceola, Wi, 1994)

Barrymore Halpenny, Bruce, Action Stations 2: Military Airfields of Lincolnshire and the East Midlands (Wellingborough, 1981)

Berry, Adam G R, And Suddenly They Were Gone (Boston, UK, 2015)

Berry, Adam G R, and Hans Den Brok, A Breathtaking Spectacle (Boston, UK, 2019)

Chant, Chris, Airborne Operations, ed. by Philip de Ste Croix, Paperback (London, 1982)

Dear, Ian, and M R D Foot, The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford, 1995)

Delve, Ken, Military Airfields of Britain (Ramsbury, 2008)

Ford, Ken, Steve Zaloga, and Stephen Badsey, Overlord : The D-Day Landings (Oxford, 2009)

Freeman, Roger A, UK Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now (1994)

———, UK Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now (1994)

Gregory, Barry, and John Batchelor, Airborne Warfare 1918-1945 (London, 1979)

Hamlin, John F, Support and Strike! A Concise History of the US Ninth Air Force in Europe (Peterborough, 1991)

Holmes, Richard, The Story of D-Day, 6 June 1944 (London, 2004)

Kent, Ron, First in - the Airborne Pathfinders, 2nd edn (Barnsley, 2015)

Laurenceau, Marc, ‘D-Day American Airborne Operations’, D-Day Overlord, 2016 <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/air-operations/usa>

Man, John, The Atlas of D-Day1994 (London, 1994)

Marix Evans, Martin , and William Jordan, D-Day and the Battle of Normandy (Andover, 2004)

Moran, Jeff, American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II (Atglen, PA, 2004)

Mrozek, Steven J, ‘82d Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 205

Nordyke, Phil, All American, All the Way : The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005)

Otway, Terence B H , Airborne Forces of the Second World War, 1939-45, Facsimile of War Office publication of 1951 (Uckfield, 2019)

Preisler, Jerome, First to Jump (New York, 2014)

Ramsey, Winston, D-Day Volume 1 (1995)

———, D-Day Volume 2 (1995)

Rottman, Gordon L, US Airborne Units in the Mediterranean Theater 1942–44 (2006), 8

Sowrey, Frederick, ‘Pathfinders’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 416

US Army, ‘82nd Airborne Division - D-Day - Normandy - after Action Report’, D-Day Overlord (2016) <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/battle-of-normandy/after-action-reports/82nd-airborne/d-day> [accessed 8 December 2024]

Warren, John C, Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942-45, Defense Technical Information Center (Air University, Maxwell AFB, Alabama, September 1955) <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA522511.pdf> [accessed 2019]

———, Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater, Defense Technical Information Center (Maxwell AFB, Alabama, 1956) <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA438105.pdf> [accessed 8 December 2024]

Weeks, John, Airborne Equipment (Newton Abbot, 1976)

Wikipedia Contributors, ‘Parachute’, Wikipedia (2018) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parachute> [accessed 2019]

World War II | Colour Films, ‘Pathfinders | D-Day in Colour’, YouTube, 2014 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idNbxUBof_U> [accessed 11 December 2024]

Zaloga, Steven J, US Airborne Divisions in the ETO 1944–45 (Oxford, 2007)