D-Day, 6 June 1944: The Airborne Assault

BACKGROUND

It would be a long, hard slog before the western Allies were in a position to launch an assault on occupied Europe.

May-June 1940: British troops line up on the beach at Dunkirk to await evacuation. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the dark days of 1940, Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, recognized that it would need the participation of the United States in the war – with its massive resources of manpower and equipment – before a successful invasion of Europe could be mounted. He knew that the United Kingdom must hold on to its freedom in the meantime to secure a firm base for the liberation of Europe.

Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free, and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands; but if we fail then the whole world, including the United States, and all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more prolonged, by the lights of a perverted science. 1

Winston S Churchill, Prime Minister, House of Commons, 18 June 1940

- 1

UK Government, ‘War Situation - Hansard - UK Parliament’, Parliament.uk, 1940 <https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1940-06-18/debates/34c56c70-b324-4525-8f05-37f1895c6596/WarSituation?highlight=sunlit%20uplands> [accessed 26 December 2024].

We ought to have a corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops

Prime Minister Winston Churchill takes aim with a Sten gun in 1941. These were later used extensively by British Airborne Forces. (IWM H 10688)

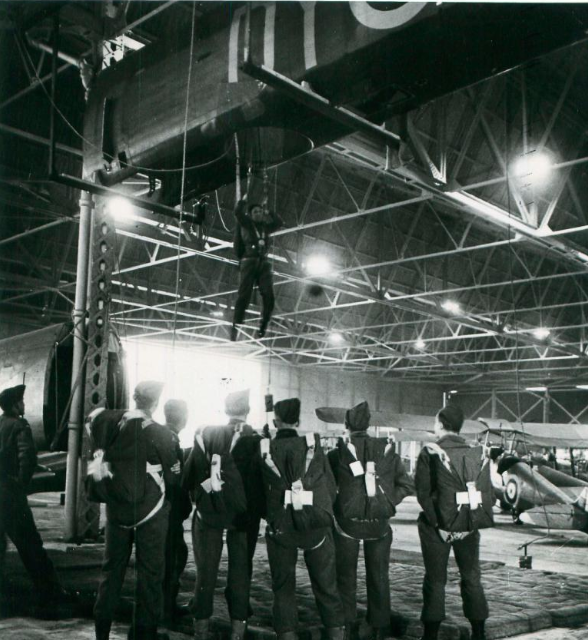

British trainee paratroopers at No 1 Parachute Training School, Ringway, Manchester. A trainee jumps from a dummy aircraft and counter-balance weights allow him to fall at the same speed as an actual jump. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

Churchill had been greatly impressed by the success of German airborne forces in the invasions of Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium. He felt that the British should develop its own parachute and glider troops to harass the enemy before and during an Allied invasion. To that end, he issued an executive order to the War Office on 22 June 1940 to set up a corps of at least 5,000 parachute troops.2 This was the green light for the UK to establish its own Airborne Forces. They would eventually develop from small units of men carrying out commando-style raids on occupied Europe to large formations of troops landing behind enemy lines to capture and hold vital terrain in advance of Allied ground forces. Two British Airborne Divisions would be established: the 1st Airborne Division in November 1941 and the 6th Airborne Division in April 1943.

Across the Atlantic, the United States Army high command had been similarly impressed with the success of German airborne troops in 1940. The US Army began developing its own airborne forces and its first Airborne Divisions were established in August 1942: the 82nd Airborne Division and the 101st Airborne Division, both of which would later be based in the UK and see combat in Europe.

By 1944, the Polish Army in the UK also had its own airborne unit: the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. It would not be used in the airborne assault on Normandy, but it was attached to the British 1st Airborne Division in July 1944 and landed at Arnhem during Operation MARKET GARDEN in September 1944.

D-Day Planning Starts

The Allied conference at Casablanca in January 1943 agreed to set up a planning staff for the invasion and liberation of Europe, and to increase the numbers of US troops sent to the UK in preparation for it.

You will enter the continent of Europe and, in conjunction with the other United Nations, undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces. 3

Directive to Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, Issued 12 February 1944

- 2

Paradata, ‘Churchill’s Letter’, Www.paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/article/churchills-letter> [accessed 26 December 2024].

- 3

Dwight D Eisenhower, Eisenhower’s Own Story of the War: The Complete Report by the Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower on the War in Europe from the Day of Invasion to the Day of Victory, Eumenes Publishing Edition (2019).

General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, speaks with Lieutenant Wallace C Strobel, a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division, at Greenham Common airfield on the evening of 5 June 1944. Shortly after Eisenhower’s visit, the men of the 101st boarded C-47 troop carrier aircraft and departed for Normandy. (Courtesy of The US National WWII Museum)

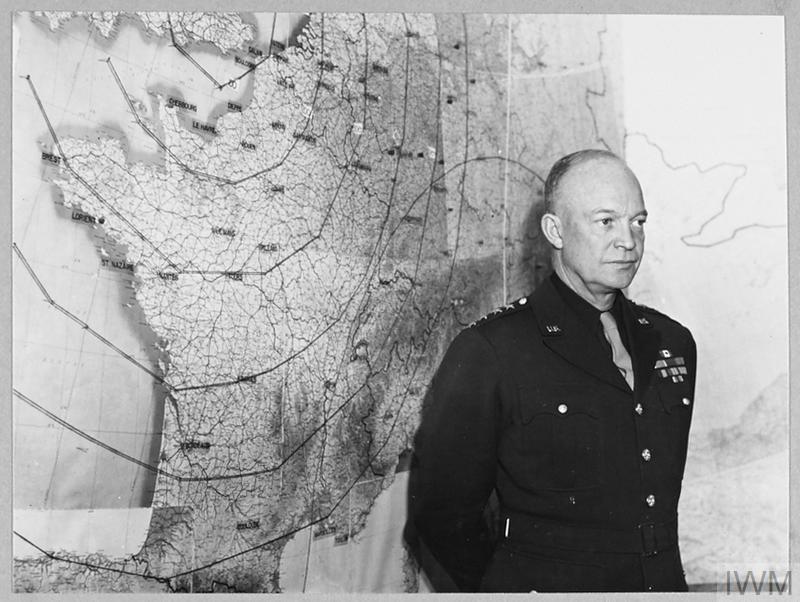

In January 1944, US General Dwight D Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces and his Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) was activated in February 1944. SHAEF directed that the liberation of north-west Europe would be called ‘Operation OVERLORD’, and the initial landings along the French coastline in Normandy would be called ‘Operation NEPTUNE’. ‘D-Day’ would be the term given to the day on which these landings would take place.

Where and When to Land?

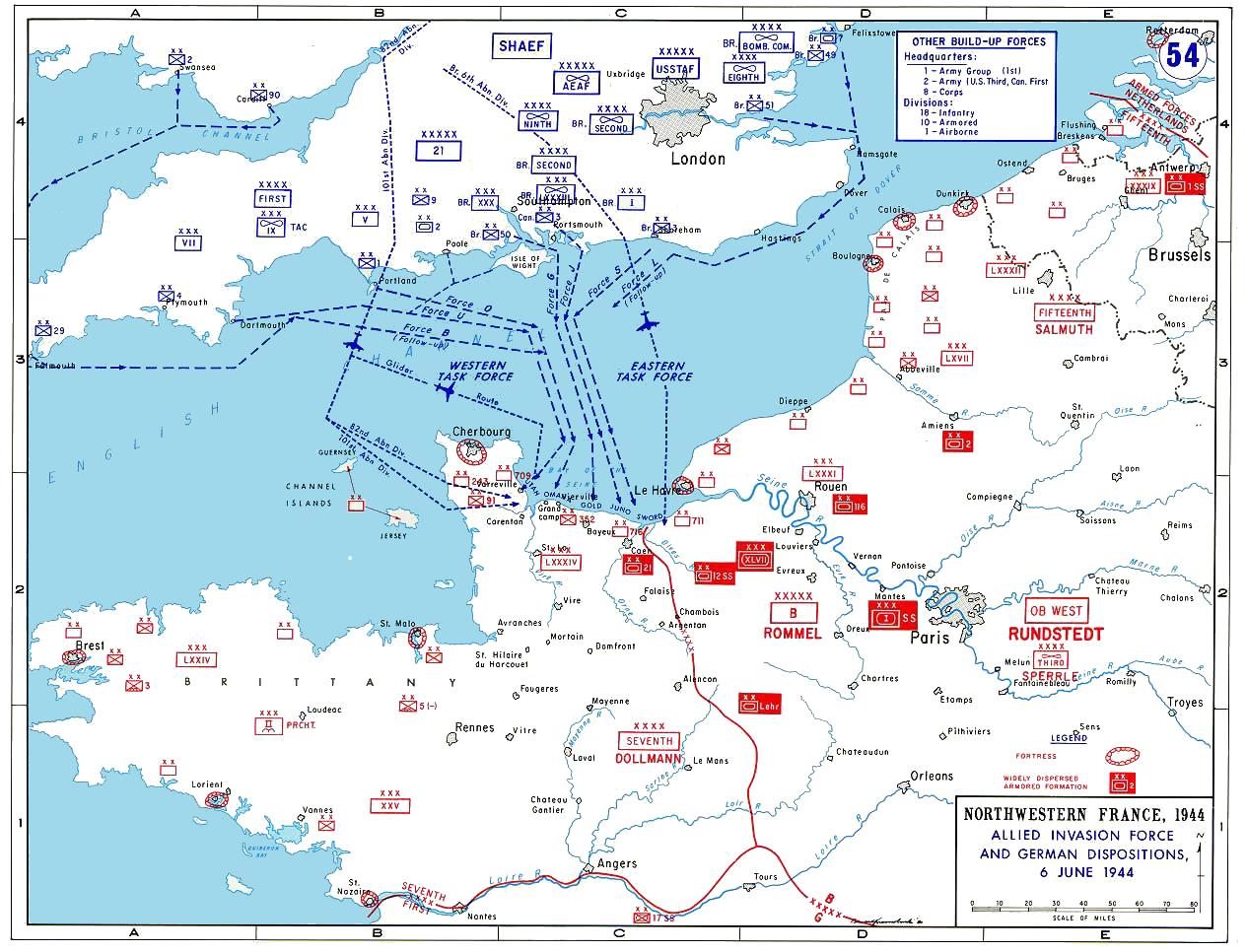

Suitable landing areas for Operation NEPTUNE would need to be within range of Allied fighter aircraft, where beach defences could be neutralized and where the Allies could rapidly land large numbers of troops. The planners did not expect to capture a major port for three months, so they needed an area that had firm, sheltered beaches where troops and stores could be offloaded and then transported inland over a reasonable road network. They eventually discovered suitable beaches in the Baie de la Seine between Cherbourg and Le Havre. Here, supplies could be landed using artificial harbours (codenamed MULBERRY) and fuel could be pumped ashore through specially laid pipelines from the south coast of England (codenamed PLUTO, standing for Pipeline Under The Ocean).

The Allies had conducted amphibious operations in the Mediterranean in 1943, and these had taken place under cover of darkness. The Normandy operation would be far larger and more complex, and Allied warships and bombers would need daylight for accurate attacks on German coastal defences. This time, the amphibious landings would occur after dawn, preceded by Airborne landings under the light of a full moon.

Dummy landing craft used as decoys in south-eastern harbours in the period before D-Day. (IWM H 42527)

Fooling the Enemy

Complex deception activities were undertaken to keep the Germans guessing as to where and when the landings would take place, both in the months before the operation and early on the day of the landings. These included:

- Feeding false information to the Germans through double agents.

- Creating fake military units.

- Deploying dummy equipment to fool aerial photography.

- Early on D-Day, dropping radar-reflective material from aircraft in set patterns to simulate landing ships away from the actual invasion fleet, and dropping dummy parachutists in areas away from the actual dropzones.

Map of the Allied D-Day landing beaches shown in blue, with German defences shown in red. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Who would be first to land?

It was decided that the US 1st and 4th Infantry Divisions, the British 3rd and 50th Infantry Divisions and the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division would spearhead the seaborne assault. These Divisions would assault beaches given the codenames (west to east) of UTAH, OMAHA, GOLD, JUNO and SWORD. Follow-on divisions would land after a beachhead had been secured.

Airborne forces would land ahead of the seaborne assault to secure the flanks of the beaches: in the west, the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions would land on the Cotentin peninsula; in the east, the British 6th Airborne Division (which included the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion) would land north-east of Caen. There would not be enough Allied aircraft to take all the paratroops and gliders simultaneously, so they would have to be transported in more than one lift.

B-26 bombers, with D-Day invasion stripes, strike a road and rail junction behind enemy lines to slow down enemy reinforcements. (USAF Museum)

The Air Campaign

Between 1 April and 5 June 1944, more than 11,000 aircraft from the Royal Air Force and the US Army Air Force flew over 200,000 sorties in support of the invasion against targets in France. They dropped 195,000 tons of bombs on rail and road communications, airfields, military installations, industrial targets, coastal batteries and radar positions. Nearly 2,000 Allied aircraft were lost but they devastated German communication and supply routes and achieved air superiority over the German air force. 4

- 4

Ian Dear and M R D Foot, The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford, 1995), 853.

General Eisenhower - Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces - in front of a map of North-West Europe at his London Headquarters in 1944. (IWM CH 12032)

By the end of May 1944, the Allies were ready to go. The need for certain tidal conditions and a full moon narrowed down the earliest landing dates to 5,6 and 7 June. Initially, 5 June was chosen but bad weather intervened and the landings were postponed for 24 hours.

At 4.00am on 5 June 1944, after much debate by senior commanders, General Eisenhower finally gave the order for the landings to start on 6 June 1944, a date that would be known to history as D-Day.5

- 5

Dwight D Eisenhower, Eisenhower’s Own Story of the War: The Complete Report by the Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower on the War in Europe from the Day of Invasion to the Day of Victory, Eumenes Publishing Edition (2019).

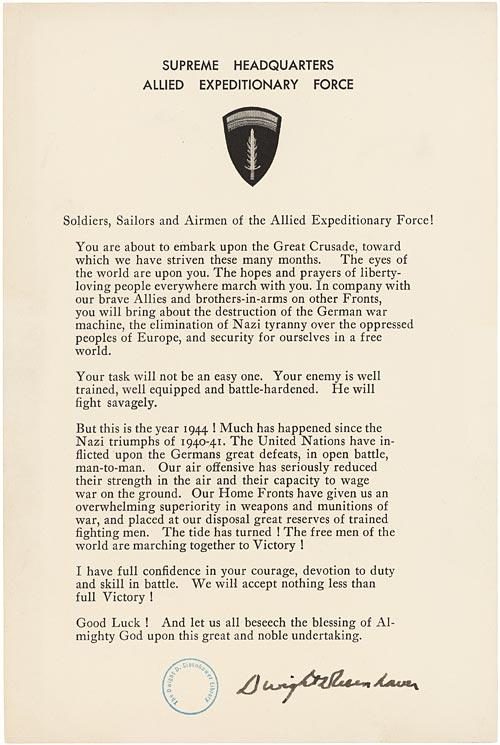

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

General Eisenhower in 1944. (US Army)

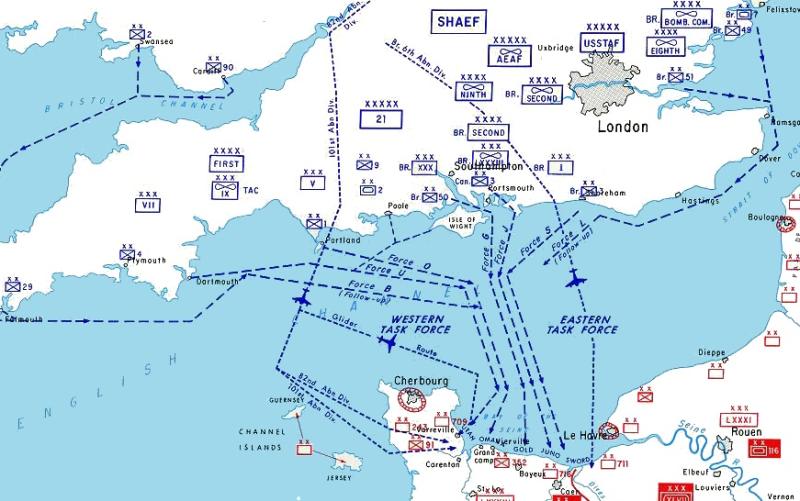

Map of the Allied D-Day invasion force shown in blue and German defences shown in red. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

THE US AIRBORNE ASSAULT

Pathfinders of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, on 5 June 1944. (US Army photo)

Pathfinders

Some of the pathfinders in the plane had their faces blackened. I did not put anything on my face. I felt if I was going to die, I wanted to die looking normal.6

Sergeant James Elmo Jones, Pathfinder, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division

The US Airborne Pathfinders were made up of specially trained volunteers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and aircrew from the US Ninth Air Force Troop Carrier Command. Their role was to land accurately on the planned drop zones (DZs) and set up electronic beacons and lights to guide in the main force of 82nd and 101st Airborne paratroopers due some 30 minutes after them. After the parachute drop, the Pathfinders would mark out the planned landing zones (LZs) for the gliders that would arrive later.

At 9.54pm Double British Summer Time on 5 June 1944, the first of 20 specially modified C-47 Pathfinder aircraft lifted off from North Witham airfield in Lincolnshire. The first C-47 was flown by Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch, commander of the Pathfinder School at North Witham, and its take-off was filmed in colour.7

The flight went according to plan as far as the west coast of the Cotentin peninsula. As the aircraft approached it around midnight, they flew into an unexpected bank of cloud, and this caused havoc with their navigation. The first Pathfinder team to jump was from the 101st Airborne and it landed at 12.20am; Pathfinders from the 82nd began landing at 1.21am.8 Overall, only two of the Pathfinder teams were dropped accurately but the remaining teams dropped close enough to their targets for them to accomplish their tasks.9

- 6

Quoted in Phil Nordyke, All American, All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 200.

- 7

World War II | Colour Films, ‘Pathfinders | D-Day in Colour’, YouTube, 2014 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idNbxUBof_U> [accessed 11 December 2024].

- 8

Marc Laurenceau, ‘D-Day American Airborne Operations’, D-Day Overlord, 2016 <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/air-operations/usa>.

- 9

Frederick Sowrey, ‘Pathfinders’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 416.

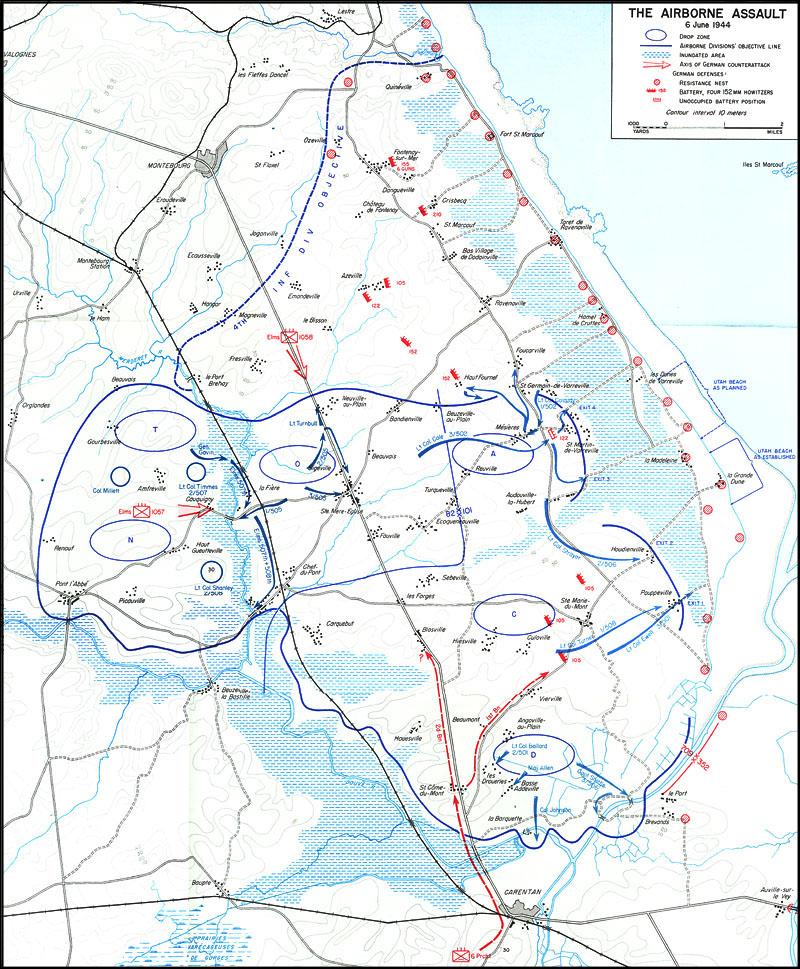

Map of the US Airborne assault on D-Day, showing US positions in blue and German positions in red. (US Army Official History)

Major General Matthew Ridgway (centre left), Commanding General, 82nd Airborne Division, and staff, overlooking the battlefield near Ribera, Sicily, 25 July 1943. (Public Domain)

US 82nd Airborne Division

I doubt very much that any major unit during the war suffered heavier casualties and kept on fighting.10

Major General Matthew B Ridgway, Commanding General, US 82nd Airborne Division in Normandy

The 82nd Airborne Division had seen combat in Sicily and Italy before arriving in Northern Ireland in December 1943 and moving to the English East Midlands in February 1944. For Operation NEPTUNE, the Division comprised the 505th, 507th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments (PIRs), the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR), plus support troops. The Division would consist of 11,979 men, including attached troops. Of this total, 6,396 were paratroopers, 3,871 were glider troops and 1,712 were troops that would be transported in ships as the Division’s seaborne ‘tail’.11

The mission of the 82nd Airborne Division during Operation NEPTUNE was to seize, clear and hold the area around the Merderet River, to the west of the small town of Ste Mère Eglise. They were to destroy all crossings of the River Douve to the south to prevent German reinforcements interfering with the initial landings and advancing northwards along the Cotentin peninsula towards Cherbourg. Afterwards, they were to prepare to move westwards when ordered.

A heavily burdened US paratrooper, armed with a Thompson M1 submachine gun, climbs into a troop carrier aircraft bound for Normandy. (Courtesy of The US National WWII Museum)

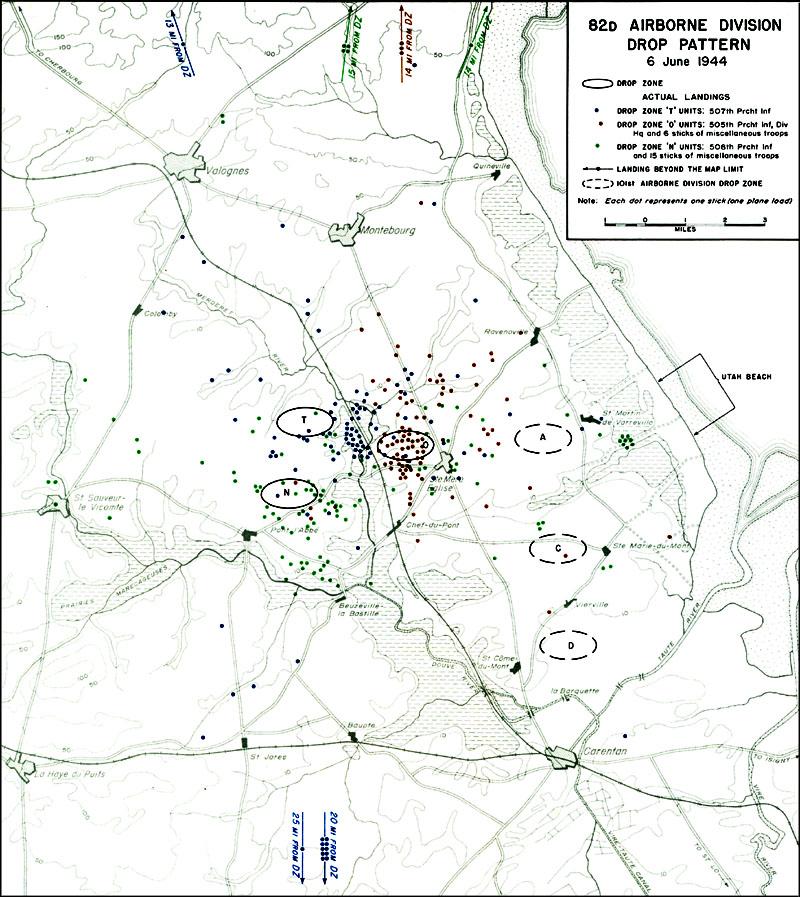

The Division’s paratroopers flew to Normandy in C-47 aircraft from seven airfields in the East Midlands: Fulbeck, Barkston Heath, Folkingham, Saltby, Spanhoe, Cottesmore and North Witham (Pathfinders). Two of their three dropzones (DZs) lay astride the Merderet River, which the Germans had used to flood surrounding land as a defence against airborne attack. The third DZ lay to the west of the small town of Ste Mère Eglise. The Division’s glider troops flew from airfields in southern England because their C-47 aircraft did not have the range to tow the gliders from as far as the East Midlands.

Within a few minutes we were gathering speed as we moved down the runway and then we were airborne and moving into position on the right wing of our element. After circling while we formed, we started on our course – sixty airplanes in two serials, carrying 950 men to France.12

1st Lieutenant Harvey Cohen, 314th Troop Carrier Group, Saltby airfield

The first aircraft carrying the main body of 82nd Airborne paratroopers took off at 1115pm on 5 June 1944.13 The cloud bank that affected the Pathfinders also prevented accurate navigation by the main force of aircraft following them. Fire from the ground increased the confusion. The first element of the main body of the Division jumped at 01.51am, 6 June 1944.14 Some pilots, fearing that they might fly past their DZs and release their troops into the sea, scattered their troops over land far away from the planned DZs. The most accurate drops were those of the 505th PIR, while troops of the 507th and 508th PIRs were widely scattered; 272 paratroopers were killed or injured in the drop.15

The opening shock of my chute was awesome. I hit the ground so hard I was numb for a couple of seconds. A German machine gun was firing away, not too far from me. But, apparently he didn’t see me because he was firing on C-47s flying low overhead.16

Private Chris Kanaras, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division

The wholesale scattering of the paratroopers caused much confusion and delay. Some of them landed in the flooded areas and drowned because their equipment was very heavy and they could not release their harnesses quickly. A lack of radios among the dispersed groups of paratroopers prevented them from communicating with each other and forming larger groups. Additionally, they had to navigate through flooded farmlands and fields with high hedgerows, and deal with surprise encounters with the enemy. As a result, only about 1,500 men of the 82nd Airborne were near their objectives by dawn on D-Day, and this number had only increased to around 2,000 by midnight.17

However, the paratroopers had been trained to exercise their initiative in situations like this. They formed themselves into improvised units and aggressively attacked enemy troops where they found them. They were reinforced by 52 CG-4A gliders with anti-aircraft and antitank guns before dawn. Of these gliders, 22 were destroyed in crashes on landing – mainly because the fields were too small - and only around 12 gliders escaped severe damage. Fortunately, eight of the guns that landed close to the zone were intact and most of them were in action by noon.18 Ste Mère Eglise was captured by dawn on 6 June 1944, becoming the first French town to be liberated.

- 12

Mark C Vlahos, Men Will Come, Second Edition (Hoosick Falls, NY, 2021), 183.

- 13

US Army, ‘82nd Airborne Division - D-Day - Normandy - after Action Report’, D-Day Overlord (2016) <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/battle-of-normandy/after-action-reports/82nd-airborne/d-day> [accessed 8 December 2024].

- 14

Ibid.

- 15

Steven J Mrozek, ‘82d Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 205.

- 16

Phil Nordyke, All American, All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 218.

- 17

Ford, Ken, Steve Zaloga, and Stephen Badsey, Overlord: The D-Day Landings (Oxford, 2009), 167

- 18

John Warren, Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater, Defense Technical Information Center (1956) <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA438105.pdf> [accessed 8 December 2024].

Map of where ‘sticks’ of 82nd Airborne paratroopers landed on D-Day (a ‘stick’ = one aircraft load). (US Army Official History)

Tightly packed troops crouch inside their landing craft as it ploughs through towards an invasion beach. (Courtesy of The US National WWII Museum)

At 6.30am, the US amphibious landings on UTAH beach commenced.

The 82nd was involved in fierce fighting throughout the day. At about 9pm - two hours before sunset - two more glider missions arrived over Normandy, one reinforcing the 82nd Airborne and one the 101st Airborne. For these missions, the Americans also used British-made Horsa gliders as well as the smaller, American-made CG-4A gliders. The Horsas had a larger cargo capacity than the CG-4As, so these glider missions carried much more cargo than the early morning missions.

By the end of D-Day, UTAH beach had been secured, but the Airborne troops were still struggling to control areas of ground inland. The 82nd Airborne’s target bridges over the Merderet River had not been secured and significant parts of the Division’s combat force were isolated to the west of the river.

Troop carrier Douglas C-47s tow Waco CG-4A gliders during the invasion of France in June 1944. (USAF Museum)

Throughout the following day, 7 June, the task of assembling and reorganizing the troops continued. The paratroopers were reinforced by glider troops of the Division’s 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, which landed early in the morning. The Division fought hard to fend off determined attacks from German troops and to establish contact with the 101st Airborne. During the day, elements of the US 4th Infantry Division advanced inland from UTAH beach against light opposition and established contact with the 82nd Airborne.

On 8 June, isolated groups of 82nd Airborne paratroopers were still fighting to the west of the Merderet River. The Division fought through to them and established a bridgehead on the west of the river on 9 June. On the same day, more reinforcements arrived when the Division’s seaborne ‘tail’ arrived in the area.

On 10 June, the US 90th Infantry Division passed westwards through the 82nd Airborne area and advanced beyond the Merderet River, taking over the bridgehead. During the fighting for this bridgehead, the 82nd Airborne had virtually annihilated the German 91st Airlanding Division. The 82nd continued to fight on the Cotentin peninsula until 8 July 1944; on 11 July, it was withdrawn to UTAH beach to prepare for return to the UK by sea.

The companies were so small standing around on the beach, they looked like platoons instead of companies.19

Private First Class Clinton Riddle, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division had started its assault on Normandy with a strength of 11,770 (not including attached troops). On D-Day, it suffered a total of 1,259 killed, wounded and missing, according to calculations made in August 1944.20 By then, the Division had been in non-stop action for 33 days and had suffered a total of 5,436 killed, wounded, sick and injured.21

US 101st Airborne Division

It wasn’t a bad landing at all, save for coming in backward and coming down right smack in the latrine for every cow in France. I must have been an awesome apparition when I finally reached cover, and how I smelled! What a stench. I had cow dung all over me. But, at any rate, I had landed, and I was still very much alive.22

Sergeant (later Lieutenant) Thomas B Buff, Headquarters Company, 101st Airborne Division

- 19

Quoted in Nordyke, Phil, All American, All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 406

- 20

Harrison, Gordon, Official History of the US Army in World War II: The European Theater of Operations: Cross-Channel Attack, Pickle Partners Publishing e-book edition (2013), 420 Note 979.

- 21

Quoted in Nordyke, Phil, All American, All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 406

- 22

Quoted in Leonard Rapport and Arthur Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny: A History of the 101st Airborne Division, Kindle edition (2015), 156.

Image: General Maxwell D Taylor, Commanding General, 101st Airborne Division. // US National Archives (213260115)

The 101st Airborne Division arrived in England from the United States in September 1943 and was based in Berkshire and Wiltshire. Its original commander was Major General William Lee, but he suffered two heart attacks and was replaced by Major General Maxwell Taylor before D-Day.

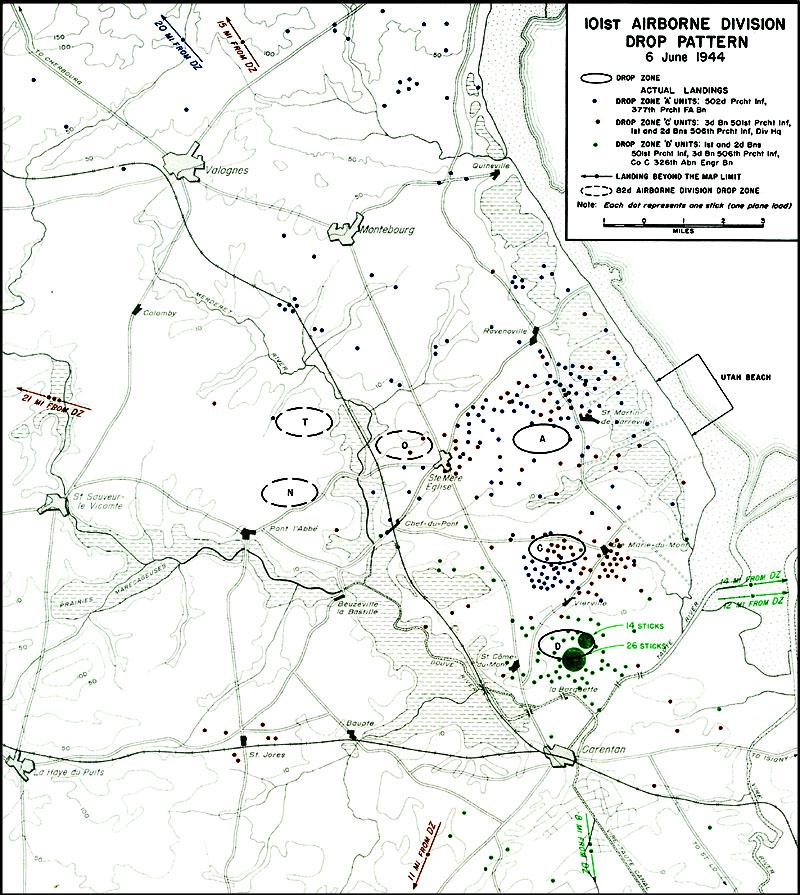

The Division comprised the 501st, 502nd and 506th PIRs, the 327th GIR, plus support troops. For Operation NEPTUNE, the Division’s primary mission was to capture and hold land immediately behind UTAH beach, which was on the east coast of the Cotentin peninsula, and the four causeways leading inland from it. The US 4th Infantry Division was due to land on UTAH beach and the area behind it had been flooded by the Germans as an obstacle; the four causeways from the beach through this flooded area were the only practicable routes inland.

A secondary objective for the Division was to protect the southern flank of the UTAH landings. To do this, the Division would have to destroy two bridges on the road to Carentan and a railway bridge to the west of the town, take control of the lock at La Barquette on the River Douve northeast of Carentan, and establish a bridgehead over the Douve.23

- 23

Ford, Ken, Steve Zaloga, and Stephen Badsey, Overlord: The D-Day Landings (Oxford, 2009), 135

101st Airborne paratroopers receive final instructions at Exeter airfield before leaving for Normandy. (US Army photo)

On 5 June 1944, 6,600 paratroopers of the Division embarked in 490 C-47 aircraft at airfields in southern England. Airborne by 1130pm, the C-47s crossed the Channel at 500 feet before climbing to 1,500 feet when they reached the Cotentin peninsula. Heading eastwards from the coast, they descended to 700 feet in readiness for the drop.24

All of us were a little tired because of the heavy equipment which was strapped very tightly to our bodies. Some of us attempted to snooze. Others just closed their eyes and attempted to relax as well as possible. Long, hard days lay ahead, and strength would be needed.25

Albert Krochka, Headquarters, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division

The cloud bank that affected the Pathfinders also hindered navigators in the main force of aircraft. Formations were split up and fire from the ground added to the confusion. The first paratroopers of the main force to jump were those of the 2nd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, at 12.48am.26

Like the 82nd Airborne Division, the drops of the 101st Airborne Division were widely scattered, with some men landing in flooded areas and drowning because they could not release their harnesses quickly. Only about 1,100 men of the 101st Airborne were near their objectives by dawn on D-Day, and this number had only increased to around 2,500 by midnight.27

The initiative and aggression of the paratroopers came to the fore because they had been trained to think and act independently in confused situations like this, so they formed themselves into improvised groups to achieve their objectives. By the end of D-Day, the Division had managed to achieve its primary objective of securing the land west of UTAH beach and the causeways leading inland from it.

On 8 June, units of the 101st Airborne pushed back German units from around Saint-Côme-du-Mont and consolidated their positions throughout 9 June. The Division was then tasked to capture Carentan. The assault began on 10 June, but the town was not cleared of the enemy until 12 June. On the following day, German reinforcements attacked the town and initially pushed back the 101st Airborne troops but the attack was repelled after US armoured units arrived.

On 15 June, the 101st Airborne was given a defensive role. Later in the month, it moved closer to Cherbourg and was allocated a sector of the Cotentin peninsula to patrol. The patrols were conducted until 10 July, when the Division moved by truck to UTAH beach for shipping back to England; it arrived at Southampton on 13 July.

You hit the ground running toward the enemy. You have proved the German soldier is no superman. You have beaten him on his own ground, and you can beat him on any ground.28

Major General Maxwell D Taylor, Commanding General, 101st Airborne Division, July 1944

Despite the setbacks it had faced, the 101st Airborne Division had accomplished its missions in Normandy but at high cost. On D-Day itself, the 101st Airborne Division suffered a total of 1,240 killed, wounded and missing, according to calculations made in August 1944.29 During the whole month of June 1944, the Division suffered a total of 4,670 killed, wounded and missing.30

- 24

Donald E Bain, ‘101st Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 407–10.

- 25

Mark Bando, The 101st Airborne at Normandy (Osceola, Wi, 1994),40.

- 26

Marc Laurenceau, ‘Serial 7 - 101st Airborne Division - D-Day Airborne and Airlanding Serials’, D-Day Overlord (2016) <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/air-operations/serials/serial-7> [accessed 11 December 2024].

- 27

Ford, Ken, Steve Zaloga, and Stephen Badsey, Overlord: The D-Day Landings (Oxford, 2009), 167

- 28

Leonard Rapport and Arthur Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny : A History of the 101st Airborne Division, Kindle edition (2015), 413

- 29

Harrison, Gordon, Official History of the US Army in World War II: The European Theater of Operations: Cross-Channel Attack, Pickle Partners Publishing e-book edition (2013), 402 Note 958.

- 30

Roland G Ruppenthal, United States Army in World War II - UTAH Beach to Cherbourg - 6-27 June 1944 [Illustrated Edition] (2014).

Map of where ‘sticks’ of 101st Airborne paratroopers landed on D-Day (a ‘stick’ = one aircraft load). (US Army Official History)

THE BRITISH AIRBORNE ASSAULT

Major General Richard Gale, commander of the British 6th Airborne Division. (Pegasus Archive)

British 6th Airborne Division

I think at that sort of age – I was, what, twenty, I suppose – fear doesn’t really come into it. You get a tremendous excitement and you wonder what it’s going to be like. None of us had any experience of battle at all. It was an excitement and an adventure, something we’d never done before, and I suppose you could say that everybody looked forward to it.31

Lieutenant Hubert Pond, 9th Battalion, Parachute Regiment

The 6th Airborne Division began forming in April 1943 under the command of Major General Richard Gale. It was composed of the 3rd Parachute Brigade (which the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion joined in July 1943), 5th Parachute Brigade and 6th Airlanding Brigade, plus support troops.

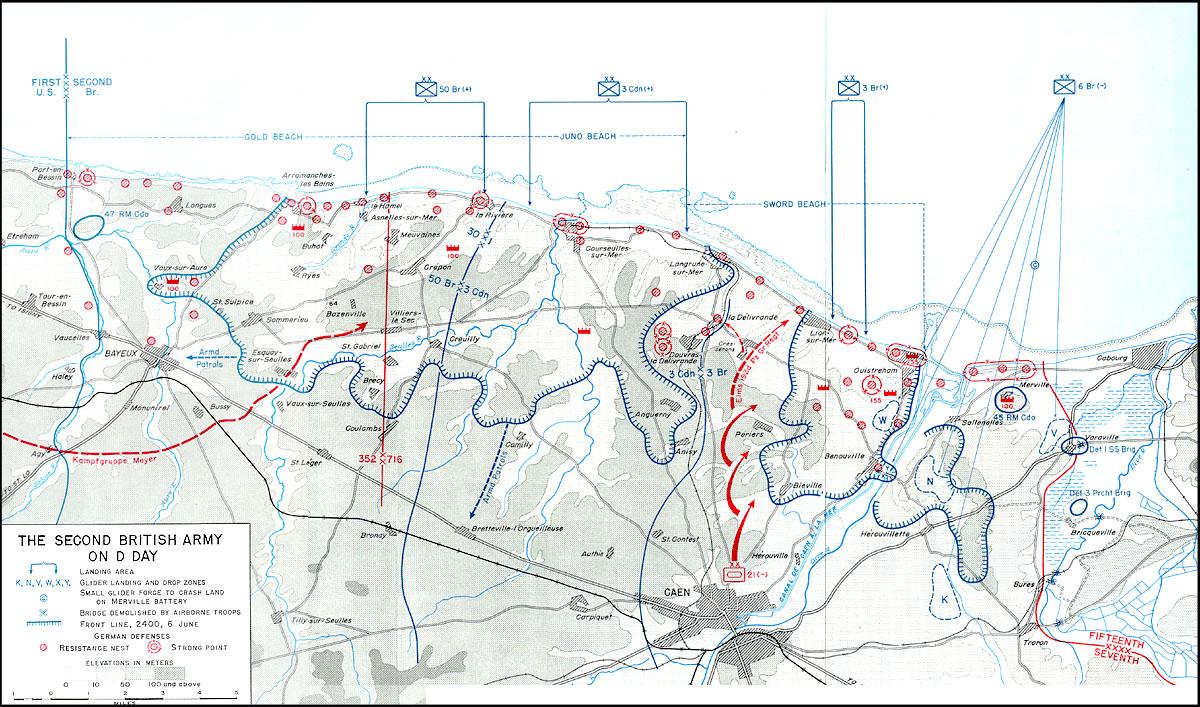

In February 1944, the 6th Airborne Division was allocated the task of defending the eastern flank of the planned British landings in Normandy. To do this, the Division was tasked with capturing intact two bridges over the River Orne and Caen Canal near Bénouville, destroying the heavy artillery emplacement at Merville, and destroying bridges over the River Dives to prevent German forces moving towards the beaches from the east and south-east.

- 31

Quoted in Roderick Bailey, Forgotten Voices of D-Day, Paperback (London, 2010), 105.

Part of 6th Airlanding Brigade, 6th Airborne Division, waiting to leave RAF Tarrant Rushton on the evening of 6 June 1944. The first two gliders are Horsas, with Hamilcar heavy gliders behind them; parked on each side of them are Handley Page Halifax glider-tugs of Nos 298 and 644 Squadrons RAF. (Royal Air Force official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

There were not enough aircraft available to carry the entire Division in one lift, so the early actions on D-Day would be conducted just by the two Parachute Brigades, with the 6th Airlanding Brigade flying in at 9pm to reinforce the Division and defend its southern flank.

The task of capturing the bridges over the Caen Canal and River Orne was given to the 5th Parachute Brigade, to which glider troops from the 2nd Battalion, Oxford & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry had been attached as a precision assault force. The destruction of the Merville gun battery was assigned to the 9th Parachute Battalion, while the 8th Parachute Battalion and 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were allocated the task of destroying five bridges over the River Dives and delaying the advance of any German troops.32

- 32

Napier Crookenden, ‘6th Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 519–21.

Map of the British landing areas, with the objectives of the 6th Airborne Division on the right. (US Army Official History)

Four Pathfinder officers synchronise their watches at about 11 pm on 5 June 1944, just prior to take off from RAF Harwell, Oxfordshire. (Capt E G Malindine, War Office official photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Pathfinders

The British 6th Airborne Division had its own permanent team of Pathfinders known as the 22nd Independent Parachute Company. In addition to finding and marking the DZs and LZs for the Division, the Pathfinders functioned as an early warning if the selected DZ was heavily defended, possibly enabling diversion to an alternative. Once the main force had landed, the Pathfinders were used as a small reserve or reconnaissance force.33 Like the 21st Independent Parachute Company of the 1st Airborne Division, the Pathfinders of the 6th Airborne Division attracted a large number of German-speaking Jewish refugees who had fled persecution in occupied countries. In the case of the 22nd Independent Parachute Company, over 60% of its personnel were Jewish refugees.34

On 6 June 1944, the Pathfinders approached the three DZs from the east and began jumping at 12.20 am. Only 30 minutes were available to erect the navigation aids before the main force was due to land, but problems arose immediately. Of the three teams of Pathfinders that should have dropped on each DZ, only one was dropped accurately and some equipment was damaged or lost. Some Eureka beacons, sending signals to the approaching aircraft, were set up on the wrong DZ, and marker lights were set up in standing crops and could not be seen from the air. A bombing raid by the RAF near one DZ almost killed the Pathfinders on it and increased confusion. As a result of all these problems, the landings of the main force were scattered.

Horsa gliders near the Caen Canal bridge (behind the trees) at Benouville, part of a force carrying troops of the 2nd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry that captured the bridges over the Orne River and Caen Canal in the early hours of D-Day. (IWM B 5233)

Operation DEADSTICK

At the same time as the Pathfinders landed on the DZs, gliders with troops from the Oxford & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry under the command of Major John Howard carried out Operation DEADSTICK: a precision landing by gliders at two bridges over the Caen Canal and River Orne. Their task was to capture the bridges intact so British troops could cross them later in the day. Through outstanding flying, most of the pilots landed their gliders within yards of their targets. The Orne bridge was undefended but a short, sharp fight ensued at the Caen Canal bridge before it was captured. The British suffered one officer killed and four men wounded. The bridge became known as Pegasus Bridge, as a mark of respect to the Airborne troops who captured it.

And above all, and this was the tremendous thing, there was no firing at all. In other words, we had complete surprise: we really caught old Jerry with his pants down.35

Major John Howard, Commander, D Company, 2nd Battalion, Oxford & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

- 35

Roderick Bailey, Forgotten Voices of D-Day, Paperback edition (London, 2010), 123.

Lieutenant Richard Todd, 7th (Light Infantry) Battalion, Parachute Regiment. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

At 3am, troops of the 7th Parachute Battalion arrived at the Canal bridge to reinforce Howard’s men, and they spent the rest of the day fighting off a series of German attacks.36 The first man of the Battalion to jump into France was Lieutenant Richard Todd, who later became a famous actor and who played Wing Commander Guy Gibson in the 1955 film, The Dambusters. He died in 2009 and is buried in St. Guthlac Churchyard, Little Ponton, South Kesteven, Lincolnshire.

At noon, men of the 1st Special Service Brigade (commandos) linked up with the paratroopers at the Caen Canal and Orne bridges, having marched inland from SWORD Beach.

- 36

Napier Crookenden, ‘6th Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 519–21.

One of four casemates at Merville, each built to house a 100mm howitzer firing a shell weighing 2,900 kg to a maximum range of 10 km (just over 5 miles). Each howitzer could fire 8 rounds per minute. (Brian Riley)

Merville Gun Battery

The gun battery at Merville was to be attacked by the 9th Parachute Battalion. Gliders were to carry jeeps, trailers, anti-tank guns, anti-mine equipment and medical support.37 At the same time as the assault went in, an additional three gliders carrying engineers, equipment and a covering section were to land on the battery itself.38

At 12.30am, the battery was attacked by Lancaster bombers but most of the bombs landed south of the target. At 12.50am, the 9th Parachute Battalion began to jump near Varraville, but they were badly scattered. Two hours later, only 150 men – about a quarter of those jumping – had arrived at the battalion rendezvous. The Germans had about 130 troops within a strong defensive perimeter at the battery.

The odds were not good for the 9th Parachute Battalion but its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway, took the decision to press on with the attack. At 4.30am, while Otway’s troops were preparing to assault the battery, two of the three assault gliders suddenly appeared overhead (one had slipped its towline before leaving England). One glider missed the battery and landed two miles away; the other crash-landed in an orchard near the battery and was quickly engaged by an enemy patrol. At this point, Otway launched his attack.

Fighting was fierce but Otway’s men managed to capture the battery. None of the engineers or demolition equipment had arrived, so the paratroopers temporarily disabled the guns with sticks of plastic explosive to prevent them being fired quickly if they were recaptured. Only about 20 of the enemy survived the assault and the 9th Battalion had also taken heavy casualties: about 65 were killed, wounded or missing, leaving around 80 fit men to set off at 6am on the Battalion’s next task of clearing the village of Le Plein.

We felt we’d done a grand job. But afterwards you think, ‘My God, what’s happened to all the guys?’ and you start looking round to see who’s left. There might have been hundreds of people that you didn’t even know, not personally, put it that way; but then there’s another hundred or so that you did know quite personally. And then you thought, ‘My God, where’s he gone?’ 39

Company Sergeant Major Barney Ross, 9th Battalion, Parachute Regiment

Although Otway achieved his objective of silencing the battery for the initial landings, the site was re-captured by the Germans in the afternoon of D-day after the survivors of the 9th Battalion had moved off. The Germans managed to put two of the guns back into action but they could only manage two rounds in every 10 minutes, instead of the usual rate of fire of one round every 10 seconds. On 7 June, men of No 3 Commando tried but failed to recapture the battery, and it remained under German control until the Germans started to withdraw from the area in August. In the meantime, the Germans fired the guns occasionally but return fire from the Allied ships discouraged them from firing often. In any case, after the initial landings on SWORD beach and the move inland of those forces, the Merville Battery became virtually irrelevant and nothing more than a nuisance.40

- 37

Paradata, ‘A Living History of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces’, Paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/> [accessed 2024].

- 38

Gregory, Barry, British Airborne Troops, 1940-45 (London, 1974), 101

- 39

Roderick Bailey, Forgotten Voices of D-Day, Paperback edition (London, 2010), 176-177.

- 40

Carl Rymen, ‘The Merville Gun Battery and Its Role after the 9th Parachute Battalion’s Attack’, Www.pegasusarchive.org <https://www.pegasusarchive.org/normandy/repMervilleBattery.htm>.

An informal German inscription made in the wet concrete of one of the early open gun positions built in 1941. It reads: ‘Germany must live, even if we die’. The symbol of ‘V’ and laurels were a German attempt to counter the Allied ‘V for Victory’ campaign that started early in 1941: the Germans claimed the symbol stood for German victory. (Brian Riley)

The farm bridge over the River Dives at Bures, destroyed by the 3rd Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, on D-Day. (Pegasus Archive)

Bridges over the River Dives

On the eastern side of 6th Airborne’s allocated area, the 8th Parachute Battalion and 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, together with their supporting engineers, successfully demolished bridges over the River Dives before taking up defensive positions around Le Mesnil and in the Bois de Bavent.

Hamilcar gliders of 6th Airlanding Brigade land near Ranville on the evening of 6 June 1944, bringing with them the Tetrarch tanks of 6th Airborne Division's armoured reconnaissance regiment. (IWM B 5198)

6th Airlanding Brigade arrives

We landed with a crash of splintered wood and we got out quick because you’re very vulnerable when you first land. We had to kick the door open, we had to run to the edge of the field, everybody was running like hell to get away from the gliders in case they were mortared, and then we saw the very tall figure of our divisional commander, General Gale. I’ll never forget the smile on his face. ‘Welcome to France, gentlemen,’ he said.41

Sergeant James Cramer, 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles

The lift bringing in 248 gliders of the 6th Airlanding Brigade arrived just before 9pm.42 The Brigade deployed to protect the southern flank of the Division.

Airborne troops dug in next to a German signpost indicating routes bypassing Caen to the north and to the south. (Sgt Christie, No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

By the evening [of D-Day], things were quiet. It had been a strenuous few hours and anxious; but the battle had gone as we had anticipated and we all felt confident. All objectives had been captured and, what was more important, held.43

Major General Richard Gale, General Officer Commanding, 6th Airborne Division

The 6th Airborne Division held a good all-round defensive position by the end of D-Day. Its task now was to prevent any German attacks breaking through to the small but expanding beachhead. Gradually, the Division tightened its hold on the area to the east of the River Orne to provide a firm base from which larger Allied formations could advance when ready.

In early August, the 6th Airborne Division was tasked with supporting the Canadian 1st Army in its breakout eastwards, with the Division’s final objective being the mouth of the River Seine at Honfleur. On 26 August, this objective was finally achieved, bringing the Division’s task in Normandy to an end. The Division had been fighting continuously for almost three months and had suffered 4,457 casualties, of whom 821 were killed, 2,709 wounded and 927 missing.44

The performance of the 6th Airborne Division again highlighted the determination and initiative of Airborne troops. Despite the setbacks, all tasks allotted to the Division were carried out: the initial scattering of the paratroopers had not caused failure in any part of the operation.45

A Major Lesson for Future Allied Airborne Operations

Particularly in the area of the American landings, the Germans were unable to focus their efforts on a major counterattack in any one place. The German commanders believed that the landings were intended to disrupt German defensive efforts rather than to gain specific areas of ground. In this respect, they viewed the Allied Airborne assault as a success.

The Allied commanders did not share the German view. Having suffered serious difficulties operating by night in the Airborne assault on Sicily in July 1943, and now in Normandy, they decided that the problems of navigating at night outweighed the defensive benefits of darkness. As a result, all major future Airborne operations in Europe would take place in daylight.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ambrose, Stephen E, D-Day : 6 June 1944 - the Climactic Battle of World War II (New York, 1995)

———, Pegasus Bridge : D-Day : The Daring British Airborne Raid, Paperback (London, 2003)

Bailey, Roderick, Forgotten Voices of D-Day, Paperback edition (London, 2010)

Bain, Donald E, ‘101st Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 407–10

Bando, Mark, The 101st Airborne at Normandy (Osceola, Wi, 1994)

Barrymore Halpenny, Bruce, Action Stations 2: Military Airfields of Lincolnshire and the East Midlands (Wellingborough, 1981)

Beevor, Antony, D-Day - the Battle for Normandy, Kindle version (London, 2019)

Berry, Adam G R, And Suddenly They Were Gone (Boston, UK, 2015)

Berry, Adam G R, and Hans Den Brok, A Breathtaking Spectacle (Boston, UK, 2019)

Biello, D Thomas, ‘US Airborne during World War II’, Ww2-Airborne.us, 1996 <https://www.ww2-airborne.us/> [accessed 2022]

Chant, Chris, Airborne Operations, ed. by Philip de Ste Croix, Paperback (London, 1982)

Crookenden, Napier, ‘6th Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 519–21

Dear, Ian, and M R D Foot, The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford, 1995)

Delve, Ken, Military Airfields of Britain (Ramsbury, 2008)

Eisenhower, Dwight D, Eisenhower’s Own Story of the War: The Complete Report by the Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower on the War in Europe from the Day of Invasion to the Day of Victory, Eumenes Publishing Edition (2019)

Elie, Patrick, ‘Operation Overlord - Normandy 1944 : Landings Areas’, Www.6juin1944.com <http://www.6juin1944.com/assaut/en_index.html> [accessed 2023]

Ellis, L F , Victory in the West, Volume 1, Kindle Edition (London, 1962)

Ford, Ken, Steve Zaloga, and Stephen Badsey, Overlord : The D-Day Landings (Oxford, 2009)

Freeman, Roger A, UK Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now (1994)

Greenacre, John, Churchill’s Spearhead (Barnsley, 2010)

Gregory, Barry, British Airborne Troops, 1940-45 (London, 1974)

Gregory, Barry, and John Batchelor, Airborne Warfare 1918-1945 (London, 1979)

Hamlin, John F, Support and Strike! A Concise History of the US Ninth Air Force in Europe (Peterborough, 1991)

Harclerode, Peter, ‘Go to It!’ - Illustrated History of the 6th Airborne Division (London, 2000)

Harrison, Gordon, Official History of the US Army in World War II : The European Theater of Operations : Cross-Channel Attack, Pickle Partners Publishing e-book edition (2013)

Hastings, Max, Overlord : D-Day and the Battle for Normandy 1944, Hardback (London, 1989)

Hickman, Mark, ‘The 6th Airborne Division in Normandy’, Www.pegasusarchive.org, 2004 <https://www.pegasusarchive.org/normandy/frames.htm> [accessed 2024]

Holmes, Richard, The Story of D-Day, 6 June 1944 (London, 2004)

Koskimaki, George, D-Day with the Screaming Eagles, Mass Market Edition (New York, 2006)

Langworth, Richard M, Churchill in His Own Words, Paperback (London, 2012)

Laurenceau, Marc, ‘D-Day American Airborne Operations’, D-Day Overlord, 2016 <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/air-operations/usa>

———, ‘Serial 7 - 101st Airborne Division - D-Day Airborne and Airlanding Serials’, D-Day Overlord (2016)

<https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/d-day/air-operations/serials/serial-7> [accessed 11 December 2024]

Man, John, The Atlas of D-Day1994 (London, 1994)

Marix Evans, Martin , and William Jordan, D-Day and the Battle of Normandy (Andover, 2004)

Moran, Jeff, American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II (Atglen, PA, 2004)

Mrozek, Steven J, ‘82d Airborne Division’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 205

Nordyke, Phil, All American, All the Way : The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005)

Oakley, Derek, ‘1st Special Service Brigade’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 247–48

Otway, Terence B H , Airborne Forces of the Second World War, 1939-45, Facsimile of War Office publication of 1951 (Uckfield, 2019)

Paradata, ‘A Living History of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces’, Paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/> [accessed 2024]

———, ‘Churchill’s Letter’, Www.paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/article/churchills-letter> [accessed 26 December 2024]

Preisler, Jerome, First to Jump (New York, 2014)

Ramsey, Winston, D-Day Volume 1 (1995)

———, D-Day Volume 2 (1995)

Rapport, Leonard, and Arthur Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny : A History of the 101st Airborne Division, Kindle edition (2015)

Ruppenthal, Roland G, United States Army in World War II - UTAH Beach to Cherbourg - 6-27 June 1944 [Illustrated Edition] (2014)

Rymen, Carl, ‘The Merville Gun Battery and Its Role after the 9th Parachute Battalion’s Attack’, Www.pegasusarchive.org <https://www.pegasusarchive.org/normandy/repMervilleBattery.htm>

Salamander Books Ltd, D-Day, Operation Overlord (London, 1993)

Siddall, Brian, ‘Airborne in Normandy’, Airborneinnormandy.com (2006) <https://www.airborneinnormandy.com/> [accessed 2022]

Sowrey, Frederick, ‘Pathfinders’, The D-Day Encyclopedia (Oxford, 1994), 416

‘The Second Capture of the Battery • Batterie de Merville’, Batterie de Merville, 2022 <https://www.batterie-merville.com/en/the-museum/the-battery/the-second-capture-of-the-battery/> [accessed 17 December 2024]

UK Government, ‘War Situation - Hansard - UK Parliament’, Parliament.uk, 1940 <https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1940-06-18/debates/34c56c70-b324-4525-8f05-37f1895c6596/WarSituation?highlight=sunlit%20uplands> [accessed 26 December 2024]

US Army, ‘82nd Airborne Division - D-Day - Normandy - after Action Report’, D-Day Overlord (2016) <https://www.dday-overlord.com/en/battle-of-normandy/after-action-reports/82nd-airborne/d-day> [accessed 8 December 2024]

US National Archives, ‘General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Order of the Day (1944)’, US National Archives (2021) <https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/general-eisenhowers-order-of-the-day> [accessed 26 December 2024]

Vlahos, Mark C, Men Will Come, Second Edition (Hoosick Falls, NY, 2021)

Warren, John, Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater, Defense Technical Information Center (1956) https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA438105.pdf> [accessed 8 December 2024]

Weeks, John, Airborne Equipment (Newton Abbot, 1976)

———, Assault from the Sky (Newton Abbot, 1988)

Wikipedia Contributors, ‘American Airborne Landings in Normandy’, Wikipedia (2020)<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_airborne_landings_in_Normandy> [accessed 2024]

Wood, Alan, History of the World’s Glider Forces (Wellingborough, 1990)

World War II | Colour Films, ‘Pathfinders | D-Day in Colour’, YouTube, 2014 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idNbxUBof_U> [accessed 11 December 2024]

Zaloga, Steven J, US Airborne Divisions in the ETO 1944–45 (Oxford, 2007)

Map showing the amphibious and airborne routes planned for the Allied forces on Operation NEPTUNE, 6 June 1944. (US Army, public domain)

D-DAY - Useful Resources

Dropzone Normandy:

Lt Col David Hamilton visiting North Witham airfield in 2019:

Interview with the late Lt Col David Hamilton on the D-Day Pathfinder mission:

Captain Frank Lillyman:

Oral Histories from the 82nd Airborne Division on D-Day: