Operation MARKET GARDEN

THE PLAN

Scenes of jubilation as British troops liberate Brussels, 4 September 1944. The commander of the Guards Armoured Division acknowledges the crowd from his Cromwell command tank (IWM BU 479)

Operation MARKET GARDEN began on 17 September 1944 but, despite the dogged heroism of the British, Polish and US Airborne soldiers, it did not go according to plan.

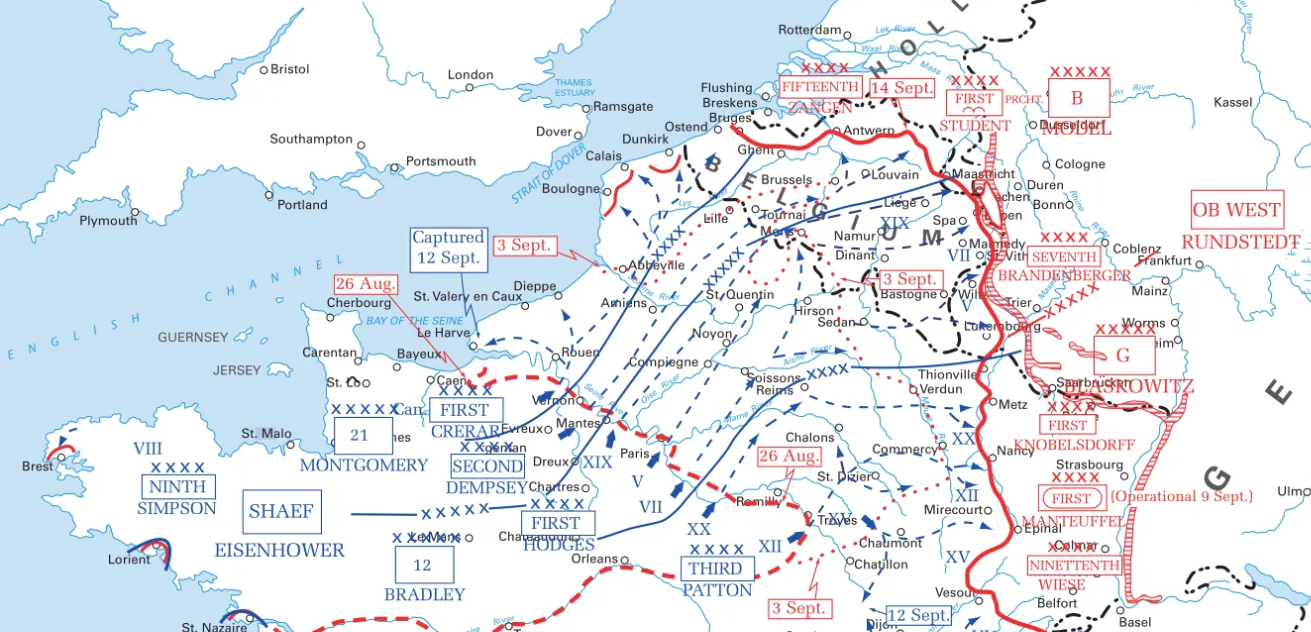

The Allies achieved major successes against the Germans in the weeks following Allied landings in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944. In some places, the fighting was bitter and hard; in others, the German forces pulled out and spared further suffering. On 15 August 1944, Allied troops landed in southern France as part of Operation DRAGOON. By 25 August 1944, when Paris fell to the Allies, large parts of France had been liberated.

There was a general feeling of elation among the Allies about the campaign in western Europe. On 1 September 1944, General Eisenhower assumed direct command of the Allied armies in western Europe, and he was very optimistic about an early end to the war.

There is no doubt whatsoever, in my mind, that we should concentrate all our energies and resources on a rapid thrust to Berlin.

General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, 15 September 1944 1

On the left flank of the Allies as they pushed forward was Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, advancing parallel to the Channel coast. Montgomery had recently been promoted to Field Marshal – at the time, the most senior British Army rank – and he was brimming with self-confidence. His spearhead units were now rushing through Belgium, the Guards Armoured Division liberating Brussels on 4 September 1944 and the 11th Armoured Division capturing intact the docks at Antwerp on 5 September. To his right, Lieutenant General Hodges had led the US First Army across the River Seine and to the edges of the Ardennes. To his south was the US Third Army under Lieutenant General Patton, at the edge of Metz, gateway to the province of Lorraine. From southern France, along the Rhône Valley, General Devers’ Sixth US Army Group was advancing northwards. By mid-September 1944, Devers had linked up with Patton, thus creating an unbroken Allied line from the Channel to the Swiss frontier. It all looked very rosy.

- 1

Quoted in Bernard Law Montgomery, The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2005), location 5206.

Map of Allied advances from Normandy to September 1944. (US Army)

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

However, there were major supply problems: the Allies were simply outstripping their logistical tail. Most of the supplies still had to be brought via the Normandy invasion beaches because many of the Channel ports were either too small to cope with the logistical demands of the Allied troops or were still held by the Germans. Even the recently captured Antwerp docks could not be used as the Germans still commanded the approaches to it through the Scheldt estuary, which stretched some 90km (56 miles) to the sea. The Americans were suffering more than the British as they were fighting further to the east and were therefore further from their supply ports.

The Allied advance was petering out and winter was looming. The poor winter weather would hamper the Allies more than the Germans because the Allies desperately needed to maintain their mobility and momentum. In contrast, the imposing static defences of the German Westwall along the western border of Germany – known by the Allies as the Siegfried Line - would allow the German defenders to shelter from both weapons and weather.

To add to the Allies’ woes, there was a major clash between their commanders over strategy. Montgomery felt that he could end the war quickly by capturing the Ruhr region - the enemy’s main industrial heartland - to stop the flow of munitions and other supplies to the German armed forces. He would then follow this with a drive across the north German plain towards Berlin. To do this, he would need priority for supplies and maintenance. Patton and other Americans commanders disagreed with this concept, preferring an advance along a broad front to gradually ‘roll up’ the enemy, and they did not want Montgomery to have priority for supplies. At first, Eisenhower opposed Montgomery’s plan, but Montgomery eventually persuaded him to agree to it. 2

- 2

Bernard Law Montgomery, The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2005),, location 5177-5186.

The major highway linking Eindhoven – Nijmegen – Arnhem would become known as ‘Hell’s Highway’ during MARKET GARDEN (Chaosdruid, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

Montgomery’s plan was designed to capture ground along the Dutch/German border, which would then be used by Montgomery’s forces as a springboard for their advance into Germany. The plan consisted of coordinated Airborne and ground assaults, and was given the overall name Operation MARKET GARDEN; its launch date was set for 17 September 1944.

The Airborne assault was called Operation MARKET and would involve surprise attacks by British, American and Polish Airborne troops of the First Allied Airborne Army, which was being held in reserve in England. It included the US 82nd Airborne Division, US 101st Airborne Division and British 1st Airborne Division, which had the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade attached to it. They were to seize and hold several vital river and canal crossings along a 100km (60 mile) corridor stretching northwards from the British front line in Belgium to the Dutch town of Arnhem. The captured crossings would then be used by Allied ground forces to advance northwards through the ‘Airborne corridor’ to Arnhem within 48 hours.

The assault by ground forces in support of the Airborne landings was called Operation GARDEN. It would involve three Corps of the British Second Army, with XXX Corps in the centre, advancing northwards through the ‘Airborne corridor’, reaching Arnhem four days later at the latest. It comprised one armoured and two infantry Divisions, one armoured brigade and the Royal Netherlands Brigade.

German SS troops in position in the woods outside Arnhem ready to repulse Allied Airborne troops. The 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were refitting and regrouping to the north and east of Arnhem and would be a formidable opponent despite the surprise of the Airborne landings. IWM (MH 3956)

During the planning process, Allied intelligence had identified many of the German units located in the areas to be assaulted. Although many of these units had been badly mauled in the Normandy fighting, Allied intelligence wrongly considered them to be spent formations whose morale had been smashed in recent battles. Their capacity to continue to fight fiercely and effectively was fatally underestimated. In the Arnhem area, battered but combat-hardened elements of the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen and 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg were recouping and refitting prior to moving into Germany; they would play a very important role in the German defence of Arnhem and Nijmegen.

Major General Robert E Urquhart, commanding 1st British Airborne Division, with the Pegasus airborne pennant in the grounds outside his headquarters at the Hartenstein Hotel in Oosterbeek, 22 September 1944 (IWM BU 1136)

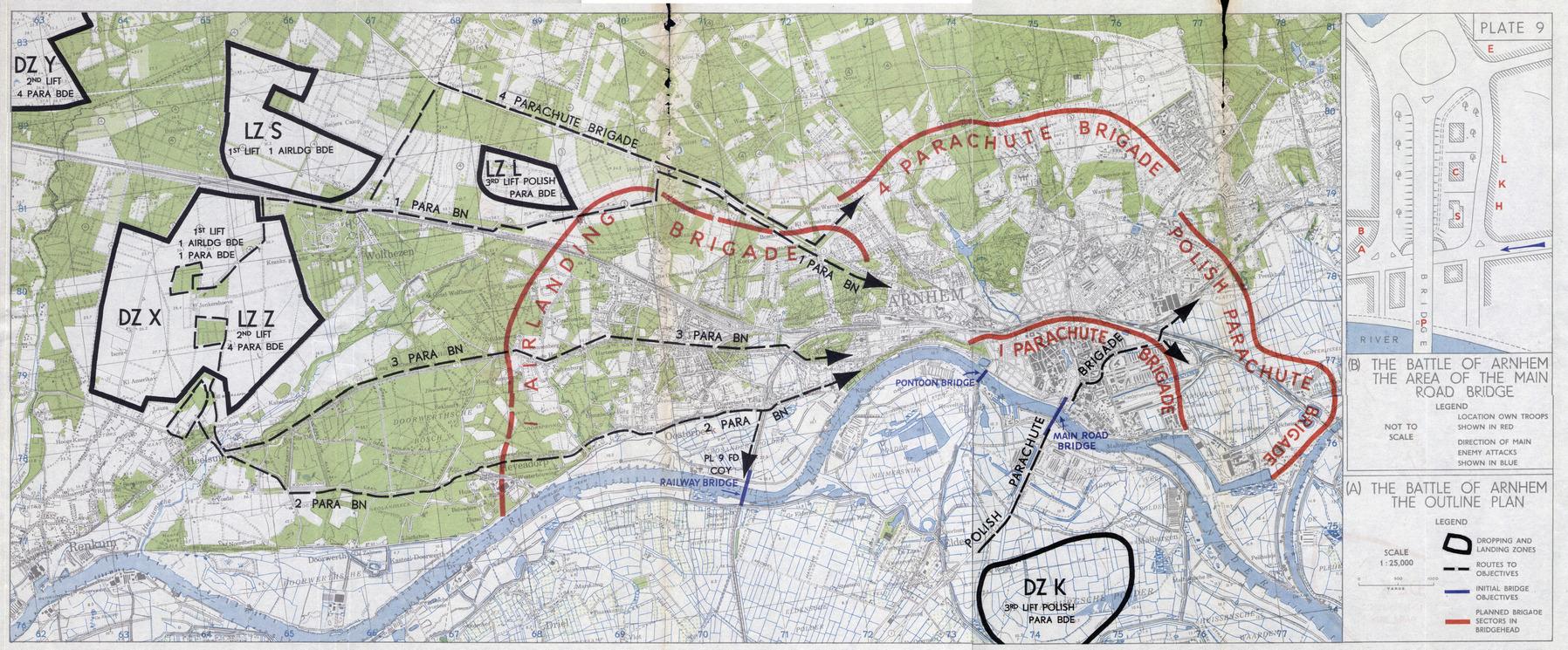

British 1st Airborne Division

The British 1st Airborne Division was commanded by Major General Robert ‘Roy’ Urquhart. Its primary combat formations were the 1st Parachute Brigade, 4th Parachute Brigade, 1st Airlanding Brigade and, for this operation, the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. The Division was tasked with capturing three bridges over the Nederrijn (Lower Rhine) river at Arnhem: the road bridge, the railway bridge and a pontoon bridge constructed close to the road bridge.

Image: 17 September 1944: General James Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, prepares his equipment before boarding a C-47 aircraft at Cottesmore for the flight to Nijmegen. // US National Archives (271813553)

US 82nd Airborne Division

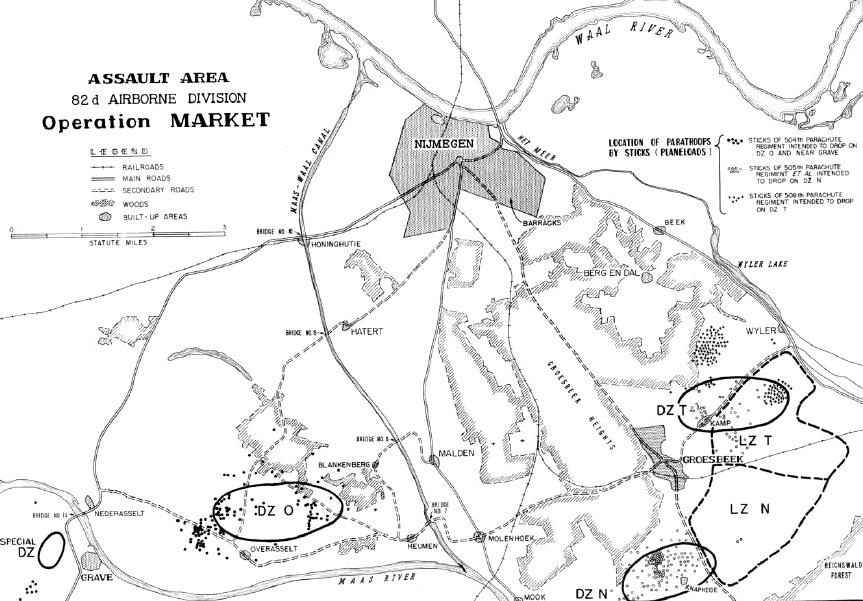

Brigadier General Jim Gavin commanded the US 82nd Airborne Division. Its combat formations comprised the 504th, 505th and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments (PIRs) and 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR). In the US Army, a Regiment was a formation roughly equivalent in size to a Brigade in the British Army. The Division was tasked with seizing the crossings of the River Maas at Grave and the River Waal at Nijmegen, as well as the canal crossing between them.

Image: General Maxwell D Taylor, Commanding General, 101st Airborne Division. // US National Archives (213260115)

US 101st Airborne Division

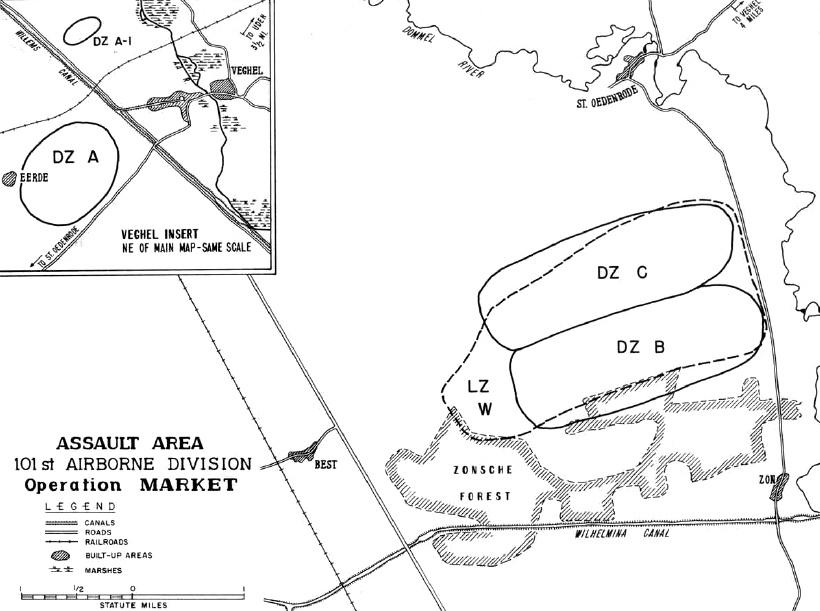

Major General Maxwell Taylor commanded the 101st Airborne Division. Its combat formations were the 501st, 502nd and 506th PIRs and the 327th GIR. The Division was tasked with securing the southernmost section of the road along which Operation GARDEN would move, channelled by the landscape into using the road from the Belgian border to Nijmegen, then nicknamed 'Hell's Highway' but nowadays known as the N69 and N265.

'Browning himself [Lieutenant General Browning, Commander, British Airborne Corps] harboured some reservations about the practicability of the whole thing. When he had been given his orders in Monty’s caravan the day before, he asked how long we would be required to hold the Arnhem Bridge. ‘Two days,’ said Monty briskly. ‘They’ll be up with you then.’ ‘We can hold it for four,’ Browning replied. ‘But I think we might be going a bridge too far.’

Major-General Frederick Browning, commanding the British 1st Airborne Division, Netheravon, 2 October 1942. (IWM TR 174)

THE BATTLE

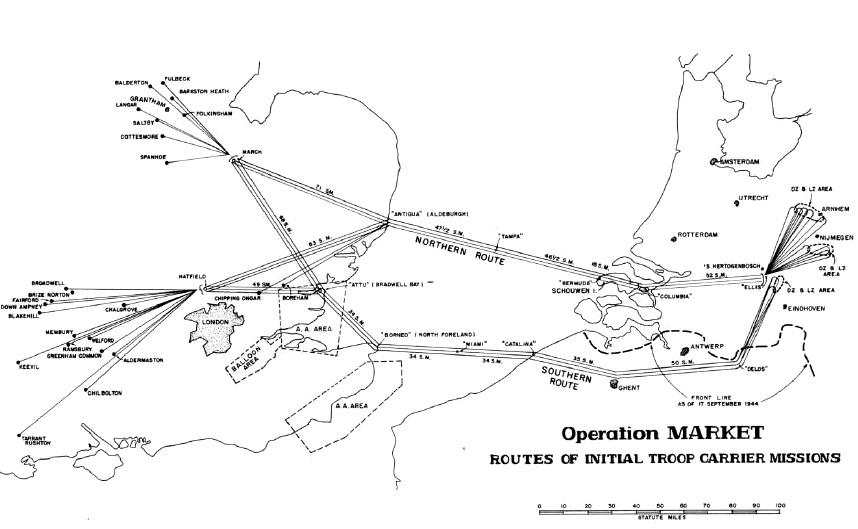

A complex network of routes was established for the Allied Airborne armada flying from England to the Netherlands. (USAF)

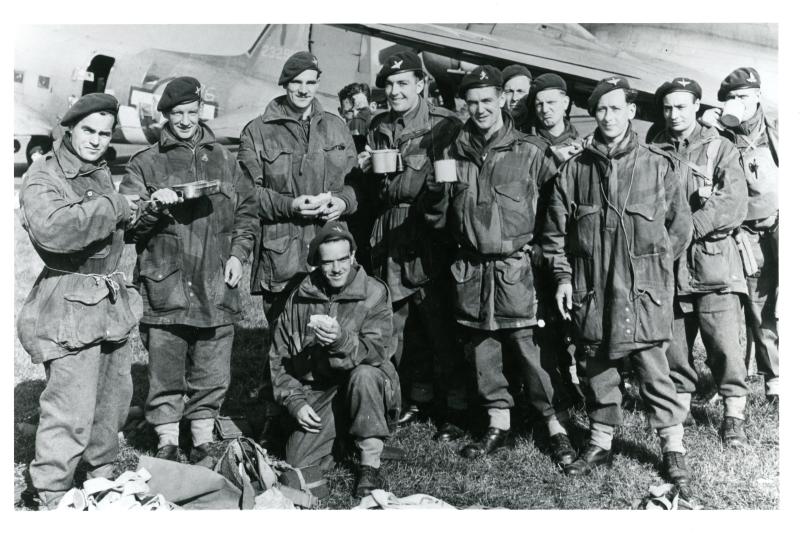

Men of the 1st Parachute Battalion enjoy a cuppa before the flight to Arnhem, 17 September 1944. Sadly, Lance Corporal Walter Lewis (kneeling) was killed in action later that day, and three others were killed during the Arnhem battle or shortly afterwards. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

17 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

Eventually we arrived at an airfield in Lincolnshire, Barkston Heath, we got off the lorry and we marched to our particular plane. I’d never seen so many aircraft on the field in my life. I think we had our parachutes issued after we de-bussed from the lorry. Some of the men were sitting quietly beside the planes and others were making jokes, eating and drinking and smoking. I remember the order being given and we all filed on to the plane. 3

Sergeant Gwilym Evans, T Company, 1st Parachute Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade

The locations of the 1st Airborne Division’s parachute drop zones (DZs) and glider landing zones (LZs) were selected specifically to minimise the threat to Allied aircraft from the German heavy anti-aircraft gun batteries believed to be near Arnhem. Unfortunately, the DZs and LZs were so far to the west of Arnhem (around 12 kilometres, about 8 miles) that a rapid advance to the bridges was hampered. Added to this was the shortage of transport aircraft and crews which meant that it would take three lifts spread over three days to bring the whole Division into the area.

- 3

Quoted in Grant R Newell, Airborne to Arnhem, Volume 1 (Warwick, 2023), 194.

Map of Arnhem showing planned dropzones, march routes and areas of responsibility for units of the 1st Airborne Division. (US Army map, public domain via https://vriendenairbornemuseum.nl/1779-2/)

17 September 1944: US C-47s of the 61st Troop Carrier Group, Barkston Heath, drop the 1st Parachute Battalion amongst some of the gliders on the edge of LZ ‘Z’. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

The first troops to land were members of the 21st Independent Parachute Company, the Pathfinders, who dropped at 12.40pm to mark out the DZs and LZs for the main body, which began to arrive at 1.15pm. This first lift brought the 1st Parachute Brigade, 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron, the Divisional Staff and most of the 1st Airlanding Brigade. The landings were virtually unopposed and losses on route had been minimal. The troops organized themselves remarkably quickly and the Reconnaissance Squadron was ordered to make a dash in its jeeps for the road bridge by way of a track just north of the railway line. However, the Squadron was stopped in its tracks east of Wolfheze by an SS training battalion under Sturmbannführer (Major) Sepp Krafft.

Meanwhile, as troops of the 3rd Parachute Battalion were making their way along the Utrechtseweg towards Arnhem, the staff car of the German Town Commandant, General Kussin, came into view. Despite being warned about the landings, the General had still taken a dangerous route; there was a short burst of fire and both he and his driver were killed. As the Battalion approached the Bilderberg Hotel, they were pinned down by Krafft's troops and remained so until nightfall, when they moved up to the Hartenstein Hotel.

By this stage, the Division and Brigade commanders had discovered that they were unable to communicate by radio and had therefore taken to racing around the battlefield in jeeps, trying desperately to keep abreast of events and remain in control.

The 1st Parachute Battalion had started along the Amsterdamseweg towards the northern approaches to Arnhem, which it was meant to secure, and soon ran into elements of the 9th SS Panzer Division. When the 1st Battalion heard on a radio, which was briefly working, that the 2nd Parachute Battalion had reached the bridge, it decided instead to go direct to the bridge to assist the 2nd Battalion.

It was now dusk and we were told to go hell for leather for the main bridge, so we raced along the last stretch with shots coming in from everywhere. We turned left up a long avenue and suddenly we were at the main bridge. After a short pause, Colonel Frost said we go over to the other side, and we climbed a steep grassy slope on the road approach and made our way slowly across. When we were about a third of the way and just going under the steel span, shell fire came at us from the German side of the bridge. 4

Private Jack Beeston, Anti-Tank Platoon, Support Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade

- 4

Quoted in Grant R Newell, Airborne to Arnhem, Volume 1 (Warwick, 2023), 223.

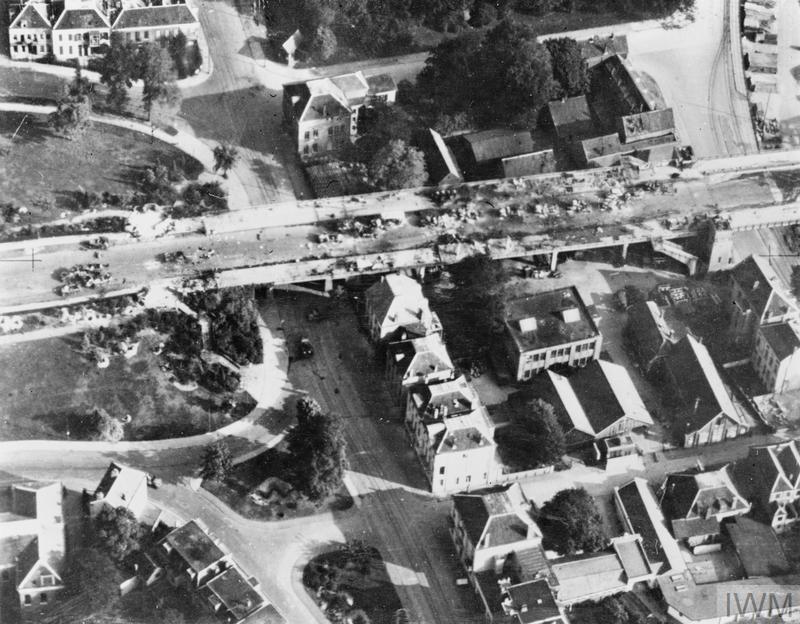

17 September 1944: RAF reconnaissance photo of Arnhem bridge, looking from the north-west, taken a few hours before the airborne landings began. (IWM CL1201, via Pegasus Archive)

The 2nd Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel John Frost had set off at 3pm from the DZ and was significantly delayed in Oosterbeek by the welcome of the Dutch. The first setback came at the railway bridge across the river, which was blown up by the Germans just as C Company reached it. A and B Companies were engaged in heavy fighting around the Den Brink heights as they attempted to force a way through to the pontoon and road bridges. It later transpired that the Germans had already removed a section of the pontoon bridge, which had rendered it unusable without engineer repairs. As darkness fell, Frost had to settle for capturing and holding only the northern end of the road bridge, filtering his men into the surrounding houses and buildings. An attempt to cross the bridge in the dark and capture the southern end was prevented by gunfire from an enemy pillbox on the bridge. An attack on this with a flame-thrower set it on fire for hours, as well as a German convoy that was trying to cross the bridge.

Paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division descending near Groesbeek on 17 September 1944. (US Army, via Wikimedia Commons)

US 82nd Airborne Division

About five minutes out, we started running into flak. Since our altitude was only five hundred feet and we were slowing to one hundred miles per hour, preparing for the jump, we were pretty easy targets. As jumpmaster, I could see every burst, I could hear the fragments as they zinged through the skin of the plane, and I sure wanted that green light to come on telling me it was time to jump. 5

Lieutenant William R Hays, Company F, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division

The 504th and 505th Parachute Infantry Regiments (PIR) assaulted and captured the bridges at Grave and the Maas-Waal Canal bridge at Heumen. The 508th PIR had been dropped near Groesbeek with the tasks of not only defending against any German counterattack along the northern edge of the Groesbeek Heights, but also moving west to help attack the objectives of the 504th and 505th PIRs. It had a further task of assaulting the Nijmegen bridge if the chance arose, but possible command misunderstandings delayed a move towards the bridge. An advance was made as night fell but elements of the 9th SS Panzer Division had already arrived from the north and successfully held off the Americans from the bridge.

- 5

Quoted in Phil Nordyke, All American, All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 434-435.

Landing zones of the 82nd Airborne Division near Nijmegen. (USAF)

Paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division crouch along a track near Best, on the look-out for enemy troops. (US Army)

101st Airborne Division

When I landed, I saw three German soldiers coming out with white flags. They were trying to surrender, but I was trying to pull my folding stock carbine from its canvas holster and shot the damn thing, almost hitting my foot. I think I was more nervous than the Germans. 6

2nd Lieutenant Robert Stroud, Company H, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division

The 502nd and 506th PIR landed between Son and St Oedenrode, whilst the 501st landed southwest of Veghel. Son fell to the 506th but the Germans blew up the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal as the Americans approached it. It was midnight before a temporary wooden bridge was completed over the Canal and the Americans chose to dig in for the night rather than attempt to attack Eindhoven in the dark; according to the plan, the town should have been taken within two hours of their landing.

One of the objectives of the 502nd PIR was the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal at Best. Enemy fire prevented them capturing the bridge and they too dug in for the night. Further north, they were more successful at St Oedenrode, where they captured the Dommel Bridge. The 501st successfully captured the canal and river bridges at Veghel.

- 6

Quoted in George Koskimaki, Hell’s Highway (Havertown, 2003), 64.

Landing zones of the 101st Airborne Division near Eindhoven. (USAF)

Sherman tanks of the Irish Guards Group advance up ‘Hells Highway’, passing others that have been knocked out. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

British XXX Corps

[Note: the British Army used Roman numerals in some organizational names during World War II; in this case, 'XXX' is the Roman numeral for '30']

The units of XXX Corps did not have an auspicious start to Operation GARDEN: within 15 mins of the start of the advance from the Meuse-Escaut Canal, nine tanks of the Guards Armoured Division were knocked out. RAF Typhoon fighter-bombers, operating in an on-call 'cab rank', were called in and silenced some of the German opposition and the advance falteringly continued. Although the Guards had liberated Valkenswaard by nightfall, it was some 10km (6 miles) south of Eindhoven, their objective for the first day; Operation MARKET GARDEN was already worryingly behind schedule.

Aerial view of the northern end of the Arnhem road bridge after the battle, showing the devastated vehicles of the 9th SS Panzer Division Reconnaissance Battalion that attempted to force a passage across the bridge from its southern end. (IWM MH 2062)

18 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

At daybreak, there were some 740 British troops around the northern end of the Arnhem road bridge, where wrecked German vehicles from the night’s fighting littered the northern ramp. At around 9.30am, the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 9th SS Panzer Division attempted to force a passage across the bridge from the southern end. The Battalion had been despatched from Arnhem on the previous day to scout towards Nijmegen to assess the strength of the enemy. Despite vigorous efforts by the Germans, they were unable to beat a way through and they left a mass of burning vehicles and dead bodies on the northern ramp.

A little further on, near a road junction, we came under attack from infantry positioned on open ground to our left and a fierce fight took place. I ran into machine gun fire and was knocked over backwards. It felt as though I had been hit over the head but in actual fact a bullet had gone straight through my helmet. It wasn’t until I tried to stand up that I realised that I had been shot through the knee. A bullet had also passed through my pack containing phosphorous bombs.

Private Bill Collard, 5 Platoon, B Company, 3rd Parachute Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade 7

Early in the morning, the 3rd Parachute Battalion attempted to push through to the road bridge from the Hartenstein Hotel, via the riverside road, Onderlangs. Its mortars, artillery and machine-guns had become separated from the main body of the Battalion so that, by the time it had reached the Pavilion on the riverbank (immediately behind the modern Rijnhotel), vital support was missing. The Battalion was pinned down by a German self-propelled gun and by German artillery firing from the brickworks on the other side of the river. At 4pm, the Battalion decided to move north into the area around St Elisabeth's Hospital. Urquhart, Brigadier Lathbury (commanding 1st Parachute Brigade) and two junior officers were trying to liaise with the 3rd Parachute Battalion at this time, but they became separated from it. Lathbury was wounded by German machine-gun firing south down Hendrickstraat and was dragged into 135 Alexanderstraat for first aid (he was later taken the short distance to the Hospital, where he was taken captive). Urquhart and his companions escaped into the house at 14 Zwaarteweg, where they were trapped in the attic overnight by a German self-propelled gun standing outside the front door! This meant that the Division commander and one of his Brigade commanders were unable to command their troops at a crucial point in the battle.

The 1st Parachute Battalion also attempted to join the 2nd Parachute Battalion at the bridge, but it came across heavy opposition while passing under the railway bridge on the lower road. It managed to push on to the area around St Elizabeth’s Hospital but no further.

Brigadier Hicks, commander of the 1st Airlanding Brigade, had assumed command of the whole Division in the absence of Urquhart and he decided to send immediately the 2nd South Staffordshire Battalion from his Brigade to help reinforce the bridge, and to send the 11th Parachute Battalion of the 4th Parachute Brigade as soon as it arrived in the second lift later that day.

I didn't know that we had been hit at first. We were all checking each other's kit, getting ready to jump; the crew chief should have been helping but he seemed to be asleep. I was angry and shouted at him and was going to kick him, but then I saw the pool of blood under his seat and realized he was dead. 8

Captain Frank King, 11th Parachute Battalion, 4th Parachute Brigade, 1st Airborne Division

A still frame from a German propaganda film showing Dutch SS troops firing at men of the 4th Parachute Brigade as they descend on Ginkelse Heide on 18 September 1944. (1944-10-04-Die-Deutsche-Wochenschau-735, Internet Archive)

The task of the 4th Parachute Brigade had originally been to occupy the high ground north of Arnhem to provide protection from any German counterattack. However, the second lift was delayed in England because of the poor weather, and it did not arrive until 3pm. Unlike the day before, there was no element of surprise, and the Brigade suffered large numbers of casualties during the landing. As the situation at the bridge was so critical, the Brigade's task was changed, and 11th Parachute Battalion was sent immediately towards the bridge and both the 10th and 156th Parachute Battalions were ordered to advance north of the railway line into Arnhem.

A CG-4A glider of the US 61st Troop Carrier Group lifts off from Barkston Heath airfield. (US Army Air Forces, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

US 82nd Airborne Division

General Gavin received warning from the Dutch Resistance that the Germans were planning to counterattack the LZs just before the glider lift landed, and so he recalled the 508th PIR from Nijmegen to protect them. Mook was taken by the 505th PIR but the Honinghutje Bridge over the Maas-Waal Canal, which would have provided an alternative route into Nijmegen, was blown up while the 504th and 508th PIRs were assaulting it.

18 September 1944: Dutch Resistance Movement soon came out of hiding to help the Allied troops as they entered the town of Valkenswaard; some of the members are seen on their way by horse and cart to assist British troops in rounding up Germans in nearby woods. (IWM BU 928)

US 101st Airborne Division

The 506th PIR entered Eindhoven, but the Division's successes were short-lived. At Best, the 502nd PIR came up against the German 59th Infantry Division and suffered heavily before the Germans blew up the bridge at around 11am.

British XXX Corps

Although the Irish Guards started to advance at 6am, their progress was very slow because fog in Belgium prevented their supporting fighter-bombers from taking off. The delays meant that it was 5.30pm before their tanks were leaving Eindhoven on route for Son, where repair work on the bridge was about to begin.

General Sosabowski and troops of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade wait in frustration at Saltby for fog to clear. (Pegasus Archive)

19 SEPTEMBER 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

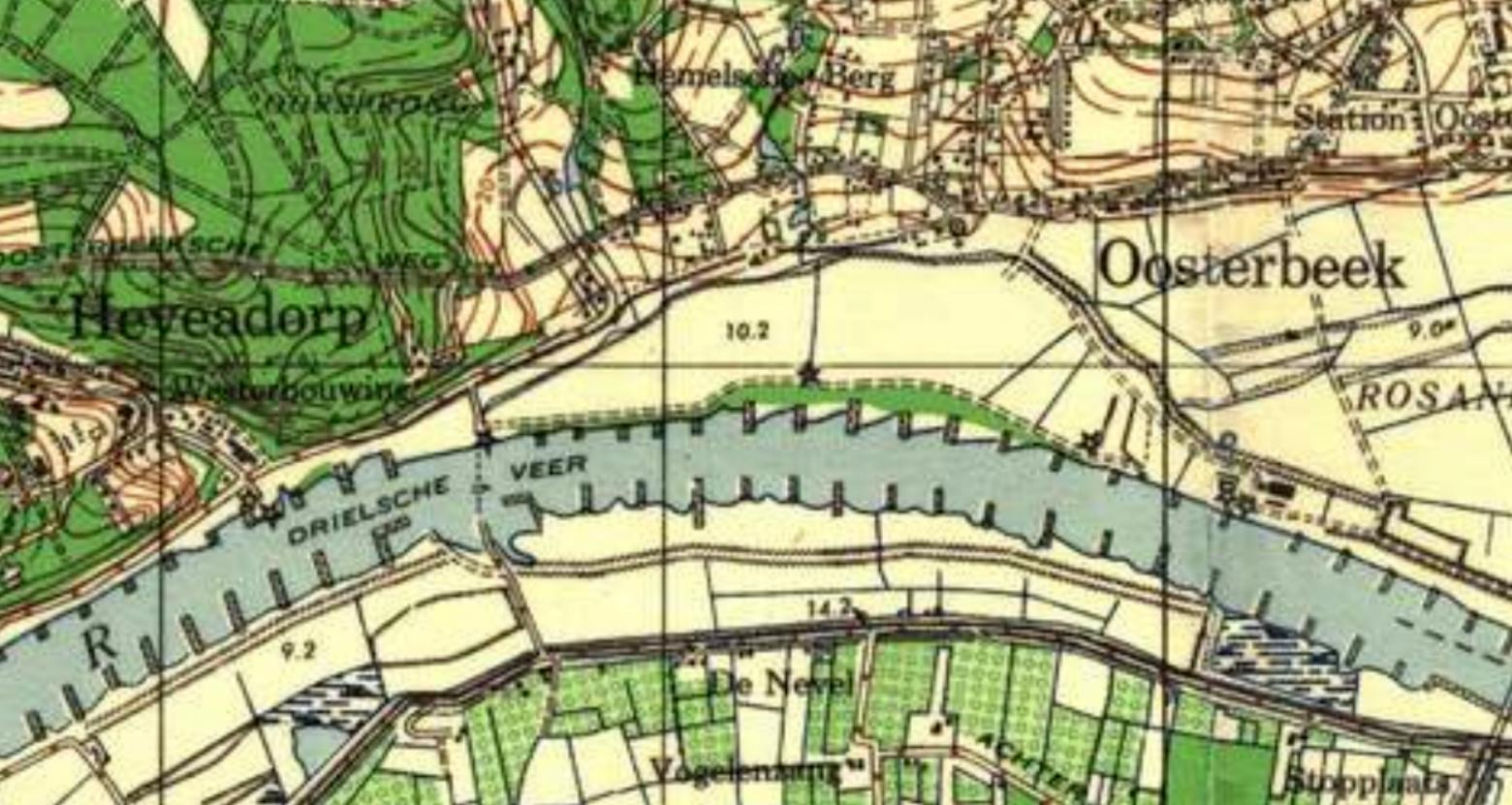

The final element of the Division - the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade - had been scheduled to drop the south of the bridge on 19 September, and help in its capture, if necessary, before crossing and moving to hold ground to the north-east of the town. However, the anti-tank support for the Brigade, largely 6-pounder guns, was to be landed on LZ 'L' to the north-west of Arnhem, some considerable distance from the Polish parachute drop. Now that the enemy held the southern part of the bridge and could not be taken by surprise, Urquhart realized that the parachute drop would probably be carnage. He therefore requested that the DZ be re-located, suggesting a site near the village of Driel on the southern side of the river, nearly opposite Oosterbeek. The suggestion was accepted.

Unfortunately, the weather intervened to prevent events going according to plan. Fog around the airfields where the Poles were waiting to take off was so bad that the parachute drop was postponed for 24 hours, and the already-emplaned Poles had to disembark from their aircraft. As the weather was better in the south of England, the Polish glider fleet was launched from the airfields of Down Ampney and Tarrant Rushton. At around 4pm, the gliders landed into heavy anti-aircraft fire but the troops moved swiftly south into Oosterbeek after unloading.

Urquhart had managed to escape back to his own forces earlier in the day. He discovered that, in his absence, Brigadier Hicks had ordered the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions to advance along the riverside road towards the bridge, while the 2nd South Staffordshire Battalion would advance along the upper road past the Hospital with the 11th Parachute Battalion behind them. The advances started at 4am but within hours they had stalled against a ferocious opposition. It was clear that it was impossible to reinforce the bridge, and the surviving British troops fell back to Oosterbeek. The Germans were slowly but relentlessly forcing the British back into a small thumb-shaped perimeter in Oosterbeek.

Flight Lieutenant David Lord VC DFC. (Courtesy of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

Throughout the day, the RAF had been carrying out supply-dropping missions. One of the Dakota aircraft involved was flown by Flight Lieutenant David Lord. His aircraft was hit by flak twice on the approach to the DZ and its right wing set ablaze. Lord carried out the drop, despite the risk of the wing collapsing, but two containers of ammunition remained on board because the despatch rollers had been damaged by enemy fire. He then made another pass over the DZ under enemy fire, before shouting to his crew to jump but the wing collapsed before the crew had time to escape. The aircraft crashed and only one of the six on board survived. He was taken prisoner and only after he, and prisoners from the 10th Parachute Battalion, were released in 1945 did the story of Lord’s bravery become known. As a result, David Lord was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, and members of his crew were awarded either a Military Cross or Military Medal.

One Dakota was hit by flak and the starboard wing set on fire. At the end of the run, the Dakota turned and made a second run to drop the remaining supplies. We were spellbound and speechless, and I dare say there is not a survivor of Arnhem who will ever forget, or want to forget, the courage we were privileged to witness in those terrible eight minutes. It was not until some time after the operation that I learned the name of the pilot of that Dakota - Flight-Lieutenant David Lord, of 271 Squadron. 9

Major General R E Urquhart, General Officer Commanding, British 1st Airborne Division

- 9

Quoted in R E Urquhart, Arnhem (Barnsley, 2008), 128.

82nd Airborne paratroopers head towards British Grenadier Guards in their joint attack on the road bridge in Nijmegen on September 19. (Public domain)

US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and XXX Corps

Dawn saw the Household Cavalry crossing the new Bailey bridge at Son but the German 59th Infantry Division at Best still threatened their advance. The 506th PIR and the 327th GIR of the 101st Airborne Division, supported by British tanks, carried out a successful attack on the enemy. The 101st Airborne also had to deal with a late afternoon attack from a German armoured brigade but, as the third lift of the Division had arrived with its artillery, the attack was repulsed.

The Guards Armoured Division reached Grave by mid-morning but had to detour via Heumen, so that it was afternoon before they could join the 505th PIR of the 82nd Airborne Division in an attack on the bridges at Nijmegen. The German defences, aided by a medieval fortification close to the bridge, were simply too strong and the attack failed. General Gavin suggested transporting his airborne troops across the River Waal in assault boats and attacking the bridge from the northern end. Although the idea was accepted, the canvas assault boats were at the rear of the massive XXX Corps column and so it would take until the following morning to get them to the front — this would mean a murderous daylight attack.

According to the original plan, XXX Corps should have been in Arnhem on Tuesday 19 September; instead, they were desperately trying to arrange an assault by airborne troops across a river in broad daylight on the following day.

Operation MARKET GARDEN was now disastrously behind schedule.

German troops close in on Arnhem road bridge. (Paradata/Airborne Assault)

20 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

The Germans had achieved complete freedom of movement in the town and artillery fire poured into Frost's men from all sides. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting had taken place around the approaches to the bridge. There were no anti-tank guns in action and the German armour had complete control. Frost himself had been wounded and the Germans were able to move freely over the bridge. During the evening, Frost gave orders for a truce to be arranged so that the wounded, which included himself, could be evacuated; the able-bodied were to fight on. Frost handed over command to Major Gough, commander of the Reconnaissance Squadron, before being taken into captivity. Throughout the night, fighting continued but it was a lost cause; as dawn arrived, those who could tried to escape back to the main force in Oosterbeek.

And as we ran out of the building there was a large explosion and that’s all I remember until waking up strapped to a German tank with another British lad who had also been wounded.This was on the Thursday morning, and by now nothing else could be expected from the 2nd Battalion. It was a terrible four and a half days, with nothing to eat, nothing to shoot with, dirty and very, very tired: we just couldn’t do any more. 10

Private Vince Goodwin, B Company, 2nd Parachute Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade

- 10

Quoted in Grant R Newell, Airborne to Arnhem, Volume 1 (Warwick, 2023), 220.

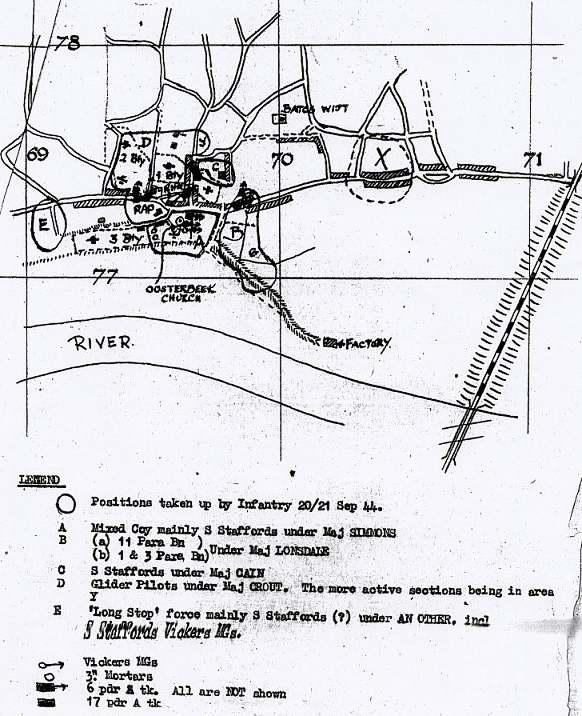

Sketch map by Lieutenant Colonel Thompson, commander of the 1st Airborne Division artillery, showing defence positions near Oosterbeek Laag church. (Pegasus Archive)

During the day, the main German effort was made by 9th SS Panzer Division, attacking along the riverside. Holding actions were fought near the church on Benedendorpsweg, where gaggles of retreating troops from the differing units were taken under the control of Lieutenant Colonel Thompson, Royal Artillery, commanding the 75mm howitzers.

A column of tanks of the British Guards Armoured Division crosses the bridge over the River Waal River at Nijmegen. (US National Archives 404790448)

US 82nd Airborne Division and XXX Corps

Further German attacks on the Son and Veghel bridges were beaten off as was an attack from Beek in the east. At Nijmegen, the Irish Guards and the 504th PIR attacked the railway bridge to the west whilst the Grenadier Guards and the 505th PIR headed for the road bridge to the east.

The water all around the boats was churned up by the hail of bullets, and we were soaked to the skin. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a boat to my right hit in the middle by a 20mm shell and sink. Somewhere to my left, I caught a glimpse of a figure topple overboard, only to be grabbed and pulled back into the boat by some hardy soul. Large numbers of men were being hit in all boats, and the bottoms of these crafts were littered with the wounded and the dead. 11

Captain Henry B Keep, 3rd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division

The assault crossing of the River Waal by the paratroopers of the 504th PIR was nothing short of staggering. The river itself is wide but beyond it there is an equally wide flood plain. In 1944, the flood plain was covered by fire from a heavily defended dyke and a strongpoint based on an old fortification. Despite this, the Americans successfully routed the defenders and went on to capture the northern end of the bridge. By 7pm, the first tanks were crossing the bridge. The Americans then expected the British armour to keep on moving at full speed towards Arnhem; instead, the British stopped and pitched camp for the night. The Americans protested vehemently but the British explained that the tanks could not fight effectively without their accompanying infantry and the Guards infantry was held up fighting in Nijmegen itself.

- 11

Quoted in Phil Nordyke, All American, All the Way : The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005), 535.

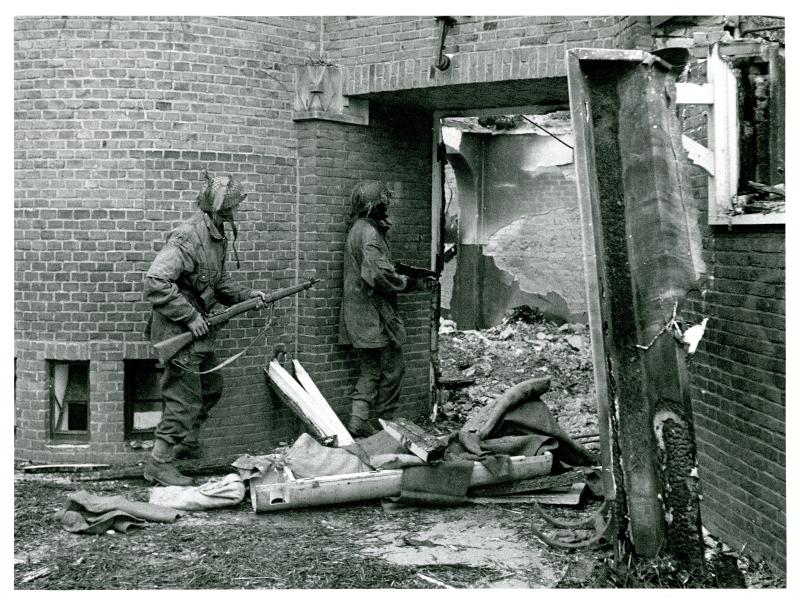

Two glider pilots enter a school on Kneppelhoutweg, in Oosterbeek, searching for snipers. The building has been hit by German mortar fire and a supply container is lying in the doorway. (Paradata/Airborne Assault)

21 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

The Germans were able to concentrate all their efforts against the Oosterbeek enclave after the end of resistance at the bridge. On the western side, the troops belonging to the Kampfgruppe von Tettau were of variable quality, but they did include a battalion of the Luftwaffe Hermann Goering NCO School, equipped with pre-war tanks. This battalion attacked the heights at Westerbouwing, defended by B Company of the 1st Battalion, Border Regiment, and eventually captured them, though they lost all their tanks in the process. Unfortunately, the loss of the heights meant that the Germans had an ideal position from which to pour fire into the enclave.

A pre-war photo of the Driel ferry on the south bank of the Lower Rhine, with the Westerbouwing heights in the background. (Gelders Archief: 1513 – 3264, Adremo, Public Domain Mark 1.0 license)

On the opposite side of the enclave, near the Oosterbeek Church, an ad hoc unit of survivors from several units had been created under the command of Major Lonsdale of the 11th Parachute Battalion. Throughout the perimeter, the front line was composed of all types of surviving troops and not just those combat troops normally involved at the frontline.

The Polish paratroopers finally dropped into Driel at 5.15pm on 21 September. The Polish 2nd Battalion headed towards the large cable ferry at the village of Heveadorp, some 11km (7 miles) west of the road bridge, intending to cross to the British troops on the northern side of the river. The ferry was normally used to carry vehicles and passengers across the Neder Rijn, but the ferry man had cut the cable on 20 September to prevent the Germans using it, and it had drifted away. Urquhart had not known this on the evening of 20 September when he was asked by higher command to nominate a new DZ and river-crossing point for the Poles.

It was dark when we reached the ferry about an hour later. We stood on the ramp, and Captain Budziszewski shouted a big ‘Hello’, but there was no reply from the other side. Then he put up a flare, but as soon as it lit up, there broke out a hell of a fire from the opposite bank. We dashed and took cover behind some heaps of cobblestones, and it was a miracle that none of us were hit. 12

Lieutenant Stefan Kaczmarek, Brigade Quartermaster, Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade

Both the Polish Parachute Brigade and the 2nd Parachute Battalion - which had passed within a few hundred metres of the ferry crossing on 17 September - were victims of a planning oversight. Divisional Intelligence knew of the ferry before the operation, noting that it was capable of carrying eight jeeps on each crossing, but it had not been made one of the objectives to be captured. It could have been used on the first day by a small jeep-mounted force to cross to the southern bank and move quickly to the other ends of the bridges, or it could have been put to later use as an additional crossing point for XXX Corps. 13 As it happened, the Poles were driven back from the river by heavy fire from the heights of the Westerbouwing and, as there was no other means of crossing the river, they dug in and awaited the inevitable German counterattacks.

XXX Corps

The roads throughout the area between the Waal and the Neder Rijn were generally built on dykes because of the marshy terrain. Consequently, the XXX Corps tanks were easy raised targets for the Germans. The Irish Guards suffered from the guns of the 10th SS Panzer Division at Elst, and infantry attempts to outflank the threats failed. Air support was unavailable because of a failure to establish communications with RAF Typhoon fighter-bombers. By nightfall, relief for the remnants of the 1st Airborne Division in Oosterbeek was no closer.

Household Cavalry armoured cars link up with Polish paratroops in Driel. (Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum)

22 SEPTEMBER 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

The presence of the Poles relieved some pressure on the perimeter as the Germans diverted units to attack them. However, as the Germans had no shortage of ammunition, they still managed to lay down heavy artillery and mortar fire into the Oosterbeek enclave, inflicting severe casualties on Urquhart's men. On the south side of the river, the marshy terrain protected the Poles, who were able to inflict close-quarter kills on German tanks on exposed roads just like those faced by XXX Corps further south. First physical contact with XXX Corps came when a handful of vehicles slipped around the German western flank to meet up with the Polish paratroopers.

During the night, an attempt was made to ferry some of the Poles across the river in rubber boats, but it failed as the current was too strong end only 52 Poles were successfully transferred to Oosterbeek before the operation was stopped.

XXX Corps

The Household Cavalry had moved west and north from Nijmegen in the morning, but their supporting infantry had come under heavy fire as they neared Oosterhout. Heavy artillery and tank support was needed to suppress the opposition, but the fighting delayed the advance until 4.30pm. Once the road was opened again, it took only 30 minutes for advance elements to reach the Poles at Driel. However, there was still no way to cross the river safely, and the troops in Oosterbeek remained out of reach.

Men of the 101st Airborne Division on the move. (US Army, public domain)

US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions

The 504th PIR was relieved from north of the Waal River and moved into the 82nd Airborne’s reserve on the south of the river. One company of the 508th PIR, with British tank support, made an unsuccessful attempt to clear the Germans from flatlands to the east of Nijmegen.

In the 101st Airborne's area, the Germans attempted to attack Veghel in a pincer movement from east and west. The Dutch Resistance forewarned the Americans and the one battalion of the 501st PIR in Veghel was boosted by the arrival of 506th PIR and 327th GIR, and they were able to drive off an attack from the north.

I still have nightmares over what might have happened if I had reacted as trained. I was sent to check out a farmhouse and to flush out any enemy snipers who might be hiding there. I burst through the door while the other two went left and right around the building. As I charged in, I saw a box-like lid raise slightly and go down very quickly. I should have sprayed the box with my tommy gun but I held back for some reason.

An old bald-headed man and his wife, and I presume their daughter with a small baby on her arm, emerged from the box which must have been an entrance to the house from the cellar.

Had I fired, as was my first impulse, the deaths of those four innocent people would have been on my mind to this day. 14

T/5 Loy Rasmussen, Company F, 506th Parachute Infantry regiment, 101st Airborne Division

The 501st and 502nd PIRs staved off further German attacks from the east and west and XXX Corps diverted the Grenadier and Coldstream Guards southwards from Uden to Veghel to clear the road of the enemy.

- 14

Quoted in George Koskimaki, Hell’s Highway (Havertown, 2003), 279.

RAF Stirling aircraft drop supplies, viewed from a garden in Oosterbeek. Sadly, most would land in enemy hands. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

23 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division

Throughout the battle, RAF transport aircraft had made valiant efforts to drop supplies to the besieged troops, losing many aircraft in the process. The last resupply flights were made on 23 September and achieved no better results than on previous days. Sadly, only 7% of the supplies dropped fell into British hands during the entire battle.

During the night a further attempt was made to ferry Polish troops across the river. Heavy fire and the late arrival of the small boats combined to make the effort a failure, with only 153 Polish paratroops crossing before the operation was cancelled.

US reinforcements arrive in CG-4A gliders. (US Army)

US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and XXX Corps

During the day, the 325th GIR and other elements of the 82nd Airborne Division were flown into Nijmegen by glider.

Along ‘Hell’s Highway’, the situation was improving with the British attacking Elst and the Americans repelling a fresh attack on Veghel; by 3pm, the road north of Veghel was open again.

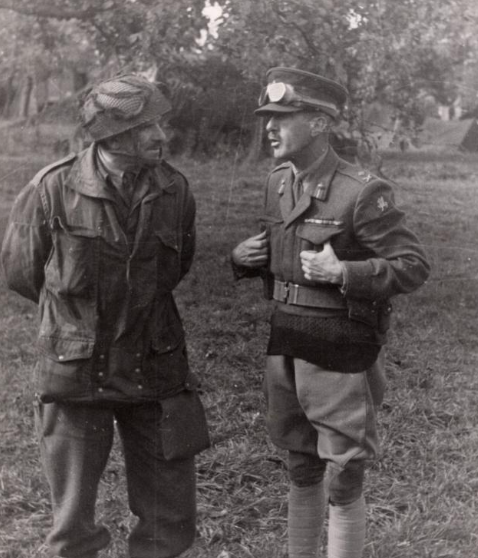

Major General Sosabowski (left) conferring with Major General Thomas. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

24 September 1944

British 1st Airborne Division and XXX Corps

In the centre of the eastern side of the enclave was a gap in the defended line at a crossroads on the Utrechtseweg. Here the Schoonoord and Vreewijk Hotels were being used by British medics as Main Dressing Stations (MDS). By 24 September, the situation in these MDS was critical and the Senior Medical Officer, Colonel Warrack, obtained Urquhart's permission to seek a truce to have the wounded evacuated. Warrack, together with the Division's Dutch liaison officer, had a personal meeting with SS General Wilhelm Bittrich, commander of the II SS Panzer Corps. Bittrich agreed to the truce and some 450 wounded were transported into German care - and captivity.

The commander of XXX Corps, Lieutenant General Horrocks, was considering the withdrawal of the 1st Airborne Division south across the Neder Rijn river. He held a meeting with Major General Stanislaw Sosabowski, commander of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, and Major General Ivor Thomas, commander of the 43rd Division. He decided the 1st Airborne Division needed reinforcing so it could hold the perimeter long enough for its troops to be withdrawn successfully across the river. Horrocks decided two battalions of infantry needed to be sent across the river into the perimeter that night. These would be the 4th Battalion, Dorset Regiment, and the 1st Polish Parachute Battalion, and both would cross beneath the Westerbouwing heights. Sosabowski was furious with the decision, believing that any attempt would be suicidal; his protests were over-ruled, and the crossing was set for 10pm. However, the assault boats arrived later than planned and were too few in number to carry the planned numbers of troops.

General Thomas started giving his more detailed orders and, turning to me, said: ‘Your 1st Battalion will go with the Dorsets.’

‘Excuse me, General,’ I retorted, ‘but one of my Battalions selected by me will go there.’ Thomas flushed red and, if it had not been for some soothing words from Horrocks, there might have been a real row. Thomas was most displeased and he very soon showed that he was not going to forget it. 15

Major General Stanislaw Sosabowski, commander of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade

- 15

Quoted in George Koskimaki, Hell’s Highway (Havertown, 2003), 279.

A Sherman tank of the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards passes a knocked-out German Panzer III tank in Oosterhout near Nijmegen, 24 September 1944. (IWM B 10375)

US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and XXX Corps

The 501st PIR was attacked at the village of Eerde, south of Veghel, and British tanks committed to assist the paratroopers suffered heavy losses. After a fight that lasted all morning, the enemy was eventually repelled, but the road was again cut by the Germans later in the afternoon. The Allies had still not dominated 'Hell's Highway'.

Around Nijmegen, the newly arrived 325th GIR was fed into the defences, as the 82nd Airborne tried to maintain its grip on land already captured.

The central part of this wartime map shows the area where survivors from the 1st Airborne Division crossed from the north to the south bank of the Lower Rhine. (US Army map, public domain, via https://vriendenairbornemuseum.nl/1779-2/)

1st Airborne Division survivors at Nijmegen, 26th September 1944. (Paradata/Airborne Assault Museum)

25 SEPTEMBER 1944

British 1st Airborne Division and XXX Corps

As the day started on the south bank of the Neder Rijn, there were only enough boats to ferry one battalion of infantry across the river into the British perimeter. The Dorset Battalion was chosen to make the crossing. Each boat would carry 10 infantrymen and be paddled by two engineers. At 1am, the Dorsets started their crossing under the cover of heavy artillery fire. Unfortunately, the barrage proved to be a double-edged sword: it set alight buildings in Heveadorp and they provided illumination of the crossing for the German defenders who poured fire onto the undefended boats. The current also took its toll and many boats overshot the perimeter and ended up in German-held areas. At 2.30am, the crossing was halted, by which time some 300 men had crossed the river. However, only a few of them had managed to join Urquhart's Division.

Fortunately, the officers carrying the authority for the evacuation of the 1st Airborne Division successfully reached Urquhart’s headquarters. The plan Urquhart created called for the troops in the north of the perimeter to withdraw first and the forces on the flanks to move last: the enclave would shrink like a balloon with the air slowly let out. The river crossing would begin at 10pm.

I realized only too well that the cost of pulling out the remnants of my division through a riverside bottleneck already reduced to between six and seven hundred yards might be high—very high.

There was no better way. 16

Major General R E Urquhart, General Officer Commanding, 1st Airborne Division

When the evacuation started, pouring rain and incessant artillery helped muffle the sounds of the troops withdrawing. Small groups of men made their way down the evacuation route, which ran along a small path past the west side of the old church in Oosterbeek and down to the river. Waiting for them on the riverbank were British engineers with paddle assault boats and Canadian engineers with motorized assault boats. As dawn broke on 26 September, some desperate men tried to swim across the river in full clothing but many of them drowned. The last boat across arrived on the south bank at around 5.30am. Of the 11,920 troops who had landed at Arnhem, only 3,910 made it back across the Neder Rijn; 1,485 were killed or died of wounds. 17

29 September 1944: Major General Urquhart (right) and glider pilots at RAF Cranwell in Lincolnshire, immediately after their flight back from Brussels on board the personal C-47 of Major-General Williams of IX Troop Carrier Command. (Pegasus Archive)

Although the British Airborne troops in Arnhem had held on at great cost far longer than the maximum four days planned, Operation MARKET GARDEN failed to achieve its overall aim of capturing ground along the Dutch/German border for use by Montgomery’s forces as a springboard for an advance into Germany.

THE CONSEQUENCES

Arnhem, 7 October 1944: photo taken during the bombing of the road bridge by a B-26 aircraft of the US 344th Bomb Group; the bridge was destroyed. (US National Archives 204916995)

The corridor, which had been so difficult to force and hold, was defended by XXX Corps and the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions into the winter. Ironically, the road bridge at Arnhem – which had cost so many lives to capture and defend - was bombed and destroyed by US aircraft on 7 October 1944 to prevent it being used by the Germans in any counterattacks.

The use of the US Airborne Divisions in a conventional infantry role was unusual and unwelcome to most of the Airborne soldiers. Over the next two months, the 82nd and 101st sustained more casualties than in Operation MARKET GARDEN itself. The Allies would have to wait until 1945 for the advances into Germany that Montgomery had hoped would follow MARKET GARDEN.

Some of the 1st Airborne troops who were left behind in Arnhem were eventually able to escape or evade capture. Many Dutch people courageously helped the evaders and escapers, and two major river evacuations were organized with their help: PEGASUS I on 22 October, when over 120 men escaped (including non-Airborne evaders), and PEGASUS Il on 18 November, which unfortunately failed and only 7 men escaped. 18

- 18

John O’Reilly, 156 Parachute Battalion from Delhi to Arnhem (Thoroton, 2009).

The Germans expelled Dutch civilians from Arnhem after the battle. Here, civilians trudge northwards from the Arnhem road bridge, with the heavily damaged St Walburgis Church in the background. (Gelders Archief: 1560 – 589, SS PK Reporter Reinsberg, Public Domain Mark 1.0 license)

The Dutch jubilation in Arnhem at the Allied landings was short-lived and the war continued for them after the fighting had ended. On 23 September 1944, the German military gave the order for civilians to evacuate Arnhem; two days later, approximately 100,000 people left the city. 19 Civilians in surrounding villages were also forced to evacuate. Many houses in the area were looted and the spoils were taken to Germany.

In retaliation, the Dutch government in Britain called for a railway strike throughout the Netherlands. The strike followed and the Germans responded by banning all inland freight movement. This had very severe repercussions for those who lived in the west of the Netherlands because food production was concentrated in the north and east of the country and could not now be transported to the west. Many Dutch civilians had to survive on a diet of potatoes, sugar-beet and tulip bulbs. As the winter progressed, the daily ration was reduced from 800 calories a day to 400, and then to 230. 20 Many did not survive the so-called ‘Hunger Winter’: an estimated 16,000-20,000 people died of starvation, but many more died from disease caused by severe malnutrition. 21

Although the Dutch had much to forgive in the wake of Operation Market Garden, their instinctive generosity to Allied troops at the time and ever since towards the veterans has been one of the most moving legacies of the Second World War. 22

Antony Beevor, historian and author

- 19

Elio, ‘Dagboek van de Arnhemse Evacuatie in 1944 - Gelders Archief’, Geldersarchief.nl (2019) <https://www.geldersarchief.nl/over-ons/actueel/weblog/428-dagboek-van-de-arnhemse-evacuatie-in-1944> [accessed 3 January 2025].

- 20

Beevor, Antony, Arnhem - the Battle for the Bridges, 1944 (London, 2019), 373, Kindle Edition.

- 21

Ibid, 379.

- 22

Ibid, 379.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barrymore Halpenny, Bruce, Action Stations 2: Military Airfields of Lincolnshire and the East Midlands (Wellingborough, 1981)

Beevor, Antony, Arnhem - the Battle for the Bridges, 1944 (London, 2019)

———, ‘Order of Battle: Operation Market Garden’, Antony Beevor, Historian <https://www.antonybeevor.com/order-of-battle-operation-market-garden/>

Berry, Adam G R, And Suddenly They Were Gone (Boston, UK, 2015)

Berry, Adam G R, and Hans Den Brok, A Breathtaking Spectacle (Boston, UK, 2019)

Buckingham, William F, Arnhem 1944 (Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2004)

Chant, Chris, Airborne Operations, ed. by Philip de Ste Croix, Paperback (London, 1982)

Cholewczynski, George F, Poles Apart (London, 1993)

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, ‘Stories of Battle of Arnhem Casualties’, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 2021 <https://www.cwgc.org/our-work/blog/stories-of-battle-of-arnhem-casualties/> [accessed 1 January 2025]

Dear, Ian, and M R D Foot, The Oxford Companion to the Second World War (Oxford, 1995)

Delve, Ken, Military Airfields of Britain (Ramsbury, 2008)

Eisenhower, Dwight D, Eisenhower’s Own Story of the War the Complete Report by the Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower on the War in Europe from the Day of Invasion to the Day of Victory, E-Book published 2019 (1946)

Elio, ‘Dagboek van de Arnhemse Evacuatie in 1944 - Gelders Archief’, Geldersarchief.nl (2019) <https://www.geldersarchief.nl/over-ons/actueel/weblog/428-dagboek-van-de-arnhemse-evacuatie-in-1944> [accessed 3 January 2025]

Freeman, Roger A, UK Airfields of the Ninth Then and Now (1994)

Frost, John, A Drop Too Many, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2009)

Fullick, Roy, Shan Hackett - the Pursuit of Exactitude, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2003)

Gelders Archief, ‘Beeldbank (Gelders Archief) - Gelders Archief’, Geldersarchief.nl (2018) <https://www.geldersarchief.nl/bronnen/foto-s-en-films?mivast=37&mizig=284&miadt=37&miview=gal&milang=nl&misort=unitdate%7Casc&mizk_alle=drielsche+veer> [accessed 2 January 2025]

Greenacre, John, Churchill’s Spearhead (Barnsley, 2010)

Gregory, Barry, British Airborne Troops, 1940-45 (London, 1974)

Gregory, Barry, and John Batchelor, Airborne Warfare 1918-1945 (London, 1979)

Hamlin, John F, Support and Strike! A Concise History of the US Ninth Air Force in Europe (Peterborough, 1991)

Hickman, Mark, ‘The Battle of Arnhem Archive’, Www.pegasusarchive.org, 2000 <https://www.pegasusarchive.org/arnhem/frames.htm> [accessed 2024]

Internet Archive, ‘1944-10-04 - Die Deutsche Wochenschau Nr. 735 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive’, Internet Archive, 2009 <https://archive.org/details/1944-10-04-Die-Deutsche-Wochenschau-735> [accessed 1 January 2025]

Jackson, Robert, Arnhem - the Battle Remembered (Shrewsbury, 1994)

Kent, Ron, First in - the Airborne Pathfinders, 2nd edn (Barnsley, 2015)

Kershaw, Robert J, A Street in Arnhem, Paperback (Addlestone, 2015)

———, It Never Snows in September (New York, 1999)

Koskimaki, George, Hell’s Highway (Havertown, 2003)

Margry, Karel, Market Garden Then and Now Boxed Set (2002)

Marix Evans, Martin, Wybo Boersma, and Adrian Groeneweg, The Battle of Arnhem (Andover, 1998)

Mcmanus, John C, September Hope : The American Side of a Bridge Too Far (New York, 2013)

Mead, Richard, General ‘Boy’ - the Life of General Sir Frederick Browning GCVO, KBE, CB, DSO, DL , Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2010)

Middlebrook, Martin, Arnhem 1944 (London, 1994)

Montgomery, Bernard Law, The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2005)

Moran, Jeff, American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II (Atglen, PA, 2004)

Newell, Grant R, Airborne to Arnhem, Volume 1 (Warwick, 2023)

Nordyke, Phil, All American, All the Way : The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II (St. Paul, Mn, 2005)

O’Reilly, John, 156 Parachute Battalion from Delhi to Arnhem (Thoroton, 2009)

Otway, Terence B H , Airborne Forces of the Second World War, 1939-45, Facsimile of War Office publication of 1951 (Uckfield, 2019)

Paradata, ‘A Living History of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces’, Paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/> [accessed 2024]

———, ‘Churchill’s Letter’, Www.paradata.org.uk <https://www.paradata.org.uk/article/churchills-letter> [accessed 26 December 2024]

Preisler, Jerome, First to Jump (New York, 2014)

Ryan, Cornelius, A Bridge Too Far, 3rd edn (London, 1978)

Saunders, Tim, The Island - Nijmegen to Arnhem (Barnsley, 2008)

Sosabowski, Stanislaw, Freely I Served, Kindle Edition (Barnsley, 2013)

St George Saunders, Hilary, The Red Beret, New English Library/Times Mirror (London, 1978)

Urquhart, R E, Arnhem (Barnsley, 2008)

Vermeer, Wilco, ‘Operation Market Garden: Third Attack on the Waal Bridges, 19 September 1944’, Tracesofwar.com (2023) <https://www.tracesofwar.com/articles/7176/Operation-Market-Garden-Third-attack-on-the-Waal-bridges-19-September-1944.htm> [accessed 2 January 2025]

Vlahos, Mark C, Men Will Come, Second Edition (Hoosick Falls, NY, 2021)

Warren, John, Airborne Operations in World War II, European Theater, Defense Technical Information Center (1956) <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA438105.pdf> [accessed 8 December 2024]

Weeks, John, Airborne Equipment (Newton Abbot, 1976)

———, Assault from the Sky (Newton Abbot, 1988)

Wood, Alan, History of the World’s Glider Forces (Wellingborough, 1990)

Zaloga, Steven J, US Airborne Divisions in the ETO 1944–45 (Oxford, 2007)